Education

Educate, agitate, negotiate: teachers unions' necessary watchwords

Strikers and protestors picket at Edinboro University for a new contract – image from YouTube

The Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties (APSCUF) had never gone on strike – until this week. After two years of contract negotiations with the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education (SSHE) ended without a contract, 5,500 professors and coaches at 14 of Pennsylvania’s colleges and universities walked off the job and onto picket lines Oct. 19 for a strike that ended on Oct. 21.

Most of the contentious issues stem from a massive state budget shortfall. The crunch began in 2011, when state and federal contributions to SSHE were cut by more than 15 percent. Gov. Tom Wolf’s budgets have provided some fiscal relief, but the deficit remains. APSCUF President Ken Mash fully acknowledges a need to trim the hedges. “There are limited resources, but chancellors and presidents certainly take salaries,” he said. “The question is how to live in this financial reality without compromising the quality of higher education in Pennsylvania. There are things at issue that are important enough for us to strike.”

Chief among them are changes that would affect adjunct faculty and graduate student teaching assistants. Mash maintains that SSHE’s latest proposal called for graduate students to teach more labs, which he sees as a first step toward using them to teach entire sections. SSHE denied this, and refuted the union’s claim that creating more online classes would marginalize professors’ roles. Meeting the increasing demand for online classes is good for higher education as a whole, it said, and would not impact in-person classrooms.

While Mash opposes SSHE’s stance on those issues, his most vehement objection is to a proposed 20 percent pay cut for adjunct faculty. In its official statements, SSHE explained the pay cut this way: “State System is proposing to adjust the pay rate for part-time, temporary faculty from $5,826 for a three-credit course to $4,660 in conjunction with our proposal for temporary faculty to no longer be required to do research and service. Even with that change, our pay rate is among the highest in the nation.”

Ken Mash – photo from YouTube

Mash wasn’t having it. “SSHE said the pay cut reflected a change in workload, but to everyone on campus, that was laughable,” he said. “They want to cut salaries for the people who get paid the least. It’s ridiculously unfair.”

Also unfair, Mash said, was a 2015 bait-and-switch deal. It originated with the one-year contract extension that AFSCME-13, the union for federal, state, county and municipal employees, signed with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in August 2015. Members got step increases – increases in salary based on commensurate experience – without conceding to increases in health care contributions. Mash would have happily agreed to that and proposed it to SSHE. But SSHE wouldn’t make that deal, and instead required health care increases. “AFSCME and other unions got that extension with no conditions,” Mash said, “so you can imagine what our reaction was.”

Generally favorable three-year contracts were ratified in August and September 2016 by AFSCME, SEIU and other municipal unions. Step increases were provided to offset a bump in health care costs, which union leaders conceded was necessary to avoid a reported $160 million deficit in the Pennsylvania Employees Benefit Trust Fund. APSCUF is not part of the fund, nor does it negotiate directly with the commonwealth, something Mash laments.

There’s no shortage of bad blood between APSCUF and SSHE. Mash contends that SSHE repeatedly acted in bad faith. “We put a comprehensive proposal on the table, and they responded with a proposal that had 249 changes,” he said. “The average number of contract changes would be about 10. We had to go through each one of those 249 items, some of which were silly and we agreed to, but some of which were clearly delay tactics.”

Mash also took issue with SSHE publishing APSCUF’s proposals on its website. “It was not a productive way to negotiate when you’re worried that any suggestion you make will be publicized,” he said. “It was plain and simple foot-dragging.” To be fair, SSHE published many of the details of its own proposals. Highlighted is an AFSCME-like proposal of raises in exchange for health care contribution increases. According to SSHE’s numbers, full-time faculty would, over a 3-year span, receive pay increases of 7.25 to 17.25 percent, which amounts to $159 million in exchange for approximately $70 million in health care and other operational changes.

SSHE doesn’t have much love for APSCUF, pointing out that the union authorized strike votes during each of its four most recent contract negotiations before agreeing to terms. SSHE also made it clear that that, by law, faculty members do not have to abide by a union strike and are free to cross picket lines and conduct classes. Mash doesn’t see that happening, saying that 82 percent of union members voted and 93 percent authorized the strike.

On the other side of the spectrum, Nina Esposito-Visgitis is looking forward to her afternoon budget meeting. Budgets are usually not chock-a-block with good news for teachers, but at least Esposito-Visgitis is meeting with city officials about her union’s next contract. That’s because she’s president of the PFT that’s not constantly in the news: the Pittsburgh Federation of Teachers. PFT400 is currently in a position that the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers envies – that of negotiating a new contract.

The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers has been without a contract for four years – or, as a recent protest T-shirt made clear, 1,000 days. The union’s last contract expired in 2012, then operated under a one-year extension. In October 2014, Philadelphia’s School Reform Commission, the body appointed by the state to oversee the city’s public schools, cancelled the collective bargaining agreement it reached with PFT. In August 2016, the state Supreme Court overturned that power play, ruling that the SRC did not have the right to do so.

What initially seemed like a victory for PFT became only the latest chapter in the ongoing contract saga. The SRC has not agreed to new negotiations, despite the union’s repeated calls for it to do so. In the meantime, the union remains stuck between a rock-like SRC and a hard place, otherwise known as Act 46: a state law that makes it illegal for Philadelphia teachers to strike.

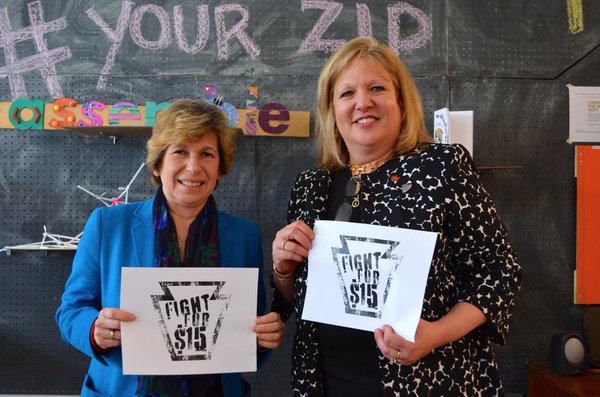

Nina Esposito-Visgitis, right, stumps for the $15 minimum wage alongside American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten – photo from Twitter

Esposito-Visgitis counts her lucky stars that she does not have to deal with an SRC-like entity. “We’re not under state takeover like Philadelphia and I’m so grateful for that,” she said. “For SRC to blame the situation on the teachers’ union makes me angry. (PFT President) Jerry Jordan is doing everything he can to get SRC back to the negotiating table and I fully empathize with him. The situation is ridiculous for Philadelphia teachers – and students.”

While Philadelphia union leadership declined repeated requests for comment, Rosemary Boland had no problem voicing her opinion. “What’s going on in Philadelphia is noticed all over the state and the country,” she said.

Boland is executive vice president of the Pennsylvania branch of the American Federation of Teachers. AFT-PA represents more than 36,000 members in 93 local affiliates, including Boland’s Local 1147 in Scranton. Boland is president of that local and led its October 2015 strike, which lasted two weeks and ended in a contract that had slight pay increases and slight healthcare cost increases. But Boland knows full well that Philadelphia teachers don’t have a strike option. “At least not one that’s legal,” she clarifies. “Teachers and other workers in Philadelphia public schools deserve better than this.”

The lack of a contract for teachers has long-term implications for Philadelphia’s public schools, Boland said. The teacher exodus, as bleakly illustrated in a recent article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, will only get worse, and attracting new teachers will continue to be difficult. “People can’t continue to work if their salaries and benefits are not looked at in a fair way,” she said. “Teachers have to think of their financial futures and those of their families. At the very least, there should be contract negotiations between PFT and the SRC.”

Esposito-Visgitis' union and the Pittsburgh School District have a productive relationship. “PFT400 has a long history of collaborating with our district,” Esposito-Visgitis said. “We have had flare-ups and disagreements, some of which were handled better than others. But we always work for the betterment of our teachers and students. SRC should learn from us.”

At issue now is PFT400’s new contract. The previous contract expired in 2015. Both sides agreed to a two-year extension, not because there were contentious issues but because a new superintendent was about to take office. “Superintendent (Linda) Lane was leaving and didn’t want to set an agenda for the new superintendent,” Esposito-Visgitis explained. “We agreed to an extension to give breathing room to Dr. (Anthony) Hamlet, the new superintendent.”

Hamlet’s tenure began in dramatic fashion: His resume came under scrutiny for discrepancies, and he was accused of plagiarism. An independent inquiry exonerated Hamlet and he was sworn into office in late June of this year, just before negotiations began with PFT400. Hamlet’s presence isn’t the only new factor. Esposito-Visgitis said there has been a lot of turnover on the school board. Because of the number of new members, both sides thought it best to use attorneys during the negotiating process. Esposito-Visgitis emphasized that they are employing – not deploying – lawyers. “I’m expecting this to be a positive and transparent situation for both sides,” she said.

All of this seems emblematic of Boland’s description of dysfunctional contract talks. Mutual respect is the necessary ingredient of successful negotiating, she said. “If respect isn’t shown for the dignity of the work on both sides, no one will agree to concessions. It’s a matter of agreeing on the reality of a financial situation, then determining what each party needs to do its work – because that work matters.”