Economic Development

Room to grow in the medical marijuana business

image: Shutterstock

Winning one of Pennsylvania’s licenses to grow or dispense medical marijuana won’t come easily or cheaply. Recreational smokers with grow lamps in their basements, young’uns looking for a “fun” business, and former flower children with impeccable pot palates but no capital need not apply.

“There’s this stereotype of the people who are involved (in the medical marijuana field) being hippies in bean bags. That is not what this industry looks like around the country,” Pennsylvania state Sen. Daylin Leach, a Democrat, said in a telephone interview. “These are serious people, intelligent people, and you’ll see a very professionally run industry.”

Gov. Tom Wolf signed the bill legalizing medical marijuana in April, with government officials predicting it would take another 18 to 24 months for the industry – including grow houses, dispensaries and related businesses – to be up and running. Pennsylvania is poised to collect a 5 percent sales tax on all medical cannabis sales, an amount dependent on demand, which is yet unknown.

But a fiscal impact report predicts the application process alone will net commonwealth coffers $10 million. Michael Bronstein, the co-founder of the American Trade Association for Cannabis and Hemp, who is working as a consultant for those looking to enter the industry, said that can cost an applicant as much as $500,000. Those who want to be considered for a license to grow also need to prove they have access to a few million dollars more to launch the business.

“It’s an expensive process,” said Bronstein. “You can’t get traditional bank financing out of this. People will have to leverage their own money or partner with private investors.”

Licensed growers will need property to grow and process their plants as well as employees to tend the buds. Dispensaries will need trained staff to recommend products to patients. Both entities will need security personnel and equipment.

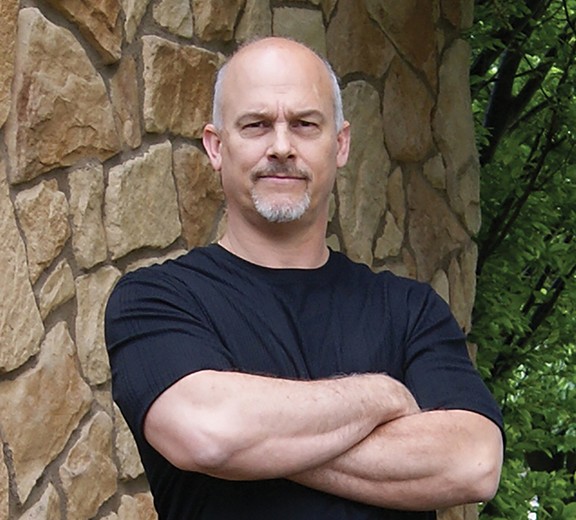

Rodney Yemc, a restaurateur in southwestern Pennsylvania, is ready for all of it. He’s spent the last two years going back and forth between the commonwealth and Colorado, gathering knowledge and investors. He’ll be submitting a application for a license to grow and process on behalf of his company, PA Cultivation Group, as soon as those forms are available. His current backers include three Colorado-based technology companies, and others have told him they’ll join the party as soon as Pennsylvania finalizes its requirements. He’s secured a 25,000 square-foot building – with a stone facade and neat landscaping – that sits on nine acres where he can grow, build and expand.

“It’s a good-looking building in a good area. I didn’t want to get some broken-down warehouse I could pick up cheap. I want to get the company off in the right direction right off the bat,” he said.

Rodney Yemc

Yemc has owned and operated his own 310-seat restaurant in Irwin, Pennsylvania, since 1991, so he knows tough businesses. Getting in on the ground floor of the new medical cannabis industry appealed to his inner entrepreneur, he said.

“It’s a very attractive thing to be early on a business. Initially I thought this would be something huge, and then you find out that it’s like every other business,” he said. “There’s no guarantees to be profitable and they’re not as high as people might believe.”

So he had to find another reason to get involved and it actually came easily, he said. “This could be a way for me to give back, to say thanks for all the success I’ve already enjoyed.”

He’s referring to the medical benefits of cannabis. Pennsylvania is the 24th state to legalize the use of marijuana for medical reasons. (Ohio would follow suit a month later.) Leach called it “the most important piece of social legislation that we’ve passed in Harrisburg in decades.” In Pennsylvania, as in other states, physicians will not “prescribe” marijuana. Instead, doctors will write a recommendation for a patient who suffers from one of 18 conditions, including chronic pain, glaucoma and epilepsy.

Leach’s support for the legalization of medical cannabis is also driven by the knowledge that it will lessen the pain for so many Pennsylvanians. Still, even now with the bill passed, he finds himself disputing claims others make about the drug.

Speaking before Philadelphia City Council’s Public Health and Human Services Committee Sept. 9, Leach still felt the need to address the idea that marijuana could be dangerously addictive during this hearing, emphasizing that the word “addiction” is often used too broadly. A frequent user of alcohol, heroin or an opioid faces severe consequences if they suddenly stop using, he said, but that’s not true even for heavy marijuana users who stop abruptly.

“It is possible for people to be dependent on it in the sense that if they don’t get it, that they get anxious, like ‘I really miss my pot,’ he noted, “but that’s not the same as physical addiction. I liken it to sex addiction – you could be like, ‘Oh my God, I really wish I could have sex.’ But you’re not going to have delirium tremens if you don’t, you’re not going to die if you don’t, you’re not going to go through cold-turkey night sweats if you don’t. You’re just going to be anxious and unhappy. I’ve been there.”

PA Sen. Daylin Leach, right, with Gov. Tom Wolf – photo courtesy of Sen. Leach

Someone suggested to Yemc that his involvement in the medical cannabis industry would hurt his restaurants. So, he said, he put that to the test, talking to newspapers and television stations in the Pittsburgh area about his plans. He said he received no negative responses and his restaurant, Rodney’s, is as busy as ever.

“People in my community know I have a good reputation and I operate a good business,” he said.

Entering the medical marijuana industry a little later in the game has given those crafting Pennsylvania’s industry guidelines an advantage, as they can look at lessons learned in states like California, Alaska, Maine and Oregon, which have allowed the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes since the late 1990s.

“The industry’s had a lot of time to develop, get its feet under it, and for people to know what are good and sensible laws that are patient-focused,” Bronstein said.

The Pennsylvania law requires that local growers have at least 10 years of experience. Since no one currently living and working here can legally claim that distinction – again, basement crops do not count – that means a local entrepreneur will need to partner with someone from outside the commonwealth to provide that institutional knowledge. The percentage of local ownership required for a partnership to be awarded a license has not been finalized, Leach said.

“We want Pennsylvania ownership and involvement, but on the other hand, we know that there’s not as much expertise in the state as there could be because it’s been illegal for 75 years,” he said. “We wanted people from outside the state to participate and give their expertise.”

That’s a smart move, said Brett Roper, founder and chief operating officer of Medicine Man Technologies, a consulting firm that has been advising companies in the cannabis business for about five years.

“We know most of the mistakes that can be made in the industry,” said Roper, who said several Pennsylvania groups have contacted his company for guidance through the application process. “Not everybody can shove a seed in a pot, put it under a light and, voilà! Three months later, we have great cannabis.”

Rosie Yagielo and her company, HempStaff, are also stepping in to fill the information void. Three years ago, she used her background in recruiting and training to launch the Florida-based company, which offers four-hour workshops at about $250 per person for those who want to work in the medical cannabis industry. She personally leads sessions about laws and regulations, and a partner who has worked in the cannabis industry in Colorado talks about recommending the right form of cannabis for a patient. The company’s first Pennsylvania sessions are scheduled for November.

“We don’t teach how to start a business,” she said, stressing that these workshops were for people seeking entry-level positions in the industry. Understanding the multitude of products and the effects they produce is essential knowledge for a dispensary worker, she said. The patient takes that recommendation to the dispensary, where an employee helps determine which form of cannabis would work best for the physician-stated condition.

After the class, attendees take a test and, if they pass, receive a laminated certificate noting that they have passed “Budtender Training and Certification.” Students can attend future classes for free to network and get updated information.

Is such training a requirement? No, Yagielo said, but in a competitive new industry, any advantage is a plus.“It helps if you show a passion for the product,” she added.

Tom Santanna, a Harrisburg-based lobbyist for the Pennsylvania Medical Cannabis Society, expects other businesses like HempStaff will pop into the state and offer training workshops. He’s attended a few and found some more helpful than others.

“But I’ve learned something new each time,” he said. “The important thing is for everyone to meet and keep learning as we get these programs rolled out.”

Roper said a workshop was a good idea for someone who doesn’t know much about the industry and wants to learn more, “but like any job competency, it’s not a matter of taking a one-day class and saying, ‘I know how to do this.’ … It’s a good first step, but most people would agree that walking away with a piece of paper doesn’t make you an expert.”

Chris Driessen, the president of O.pen Vape, the largest consumer cannabis brand in the United States, said he expects his company will partner with a Pennsylvania entity seeking a license. The Colorado-based company specializes in extracting medical-grade oil from cannabis, which is what local businesses will need to provide – smoking the product is still not legal.

There’s a lot of potential for profit here. Pennsylvania has 12.8 million residents and potentially 150 dispensaries to start. O.pen Vape is also licensed in Maine, which has 1.3 million people and three dispensaries. The company grossed more than $1 million in Maine last year.

“Your regulations are going to be very conducive to running a good program,” Driessen observed.

That will benefit everyone, Roper said. Last year, he noted, Colorado collected $130 million in taxes from cannabis-related businesses.

“This has meant an awful lot of jobs across the state of Colorado,” he said. “It’s a whole new niche of employment being created.” ■

NEXT STORY: The looming battle over immigration