The under-the-radar power players you need to know

“Power” can be a loaded word. Within its onomatopoeic impact lies one of the most, well, powerful ways to label something – or, in the case of this article, someone.

The 11 Pennsylvanians profiled within these pages all possess it, each in their own way affecting how things work within our borders. You may not recognize some of their names – and some of them like that anonymity just fine, thank you very much – but without them, the people you do recognize in Pennsylvania politics wouldn’t be where they are today.

Drew Compton

The consigliere

For two decades, the president of the Pennsylvania state Senate – no matter who holds the position – has turned to Drew Crompton for advice.

The Montgomery County native, 48, moved to Harrisburg in his early 20s for a job with the Senate Republicans’ policy office. Fifteen months later, then-senate president Robert Jubelirer’s chief counsel retired and Crompton was approached to replace him. When Jubelirer lost his primary in 2006 and current Senate President Joe Scarnati – one of the most powerful politicians in the commonwealth – rose to take his place, he kept Crompton, eventually giving him the job of chief of staff as well as counsel.

Crompton’s been in the Senate President’s office for so long, he jokes that he’s occupied just about every cubicle and office inside the sprawling suite. Instrumental in creating Pennsylvania’s mid-2000s ethics laws, his responsibilities have grown along with his experience and influence.

“I do a lot less drafting than I used to. I tell people that my role now is walking around,” says Crompton.

In 2014, Crompton was named general counsel to the Senate Republican caucus in addition to his roles with the president. His boss’ grip on this large and sometimes acrimonious mass of Republican senators is, of course, less ironclad than that of powerful party leaders of old, but as an enforcer for the powerful president pro tempore and his troops, Crompton enjoys access everywhere. He also believes that his Southeastern Pennsylvania roots help him build bridges between Scarnati, who represents a massive swath of rural northern Pennsylvania, and the more moderate wing of the delegation from the Philly region.

“I represent a guy who lives 200-plus miles from the Southeast,” says Crompton. “Having some limited appreciation of the Southeast allows me to make recommendations and advise my boss on the nuances of constituents from totally different areas of the commonwealth.”

Scarnati formerly led the caucus with Delaware County’s Dominic Pileggi, the ex-majority leader, but ran at the top of a slate against him in 2014 – a move that was seen as rejection of compromise in the wake of Gov. Tom Wolf’s election.

Those geographic distinctions matter in a state this large. The culture and politics of Bucks County are dramatically different than those of Forest or Tioga counties, even if all the politicians involved have “R’s” beside their names.

Of course, it helps that now the Republican senators all have a common opponent in Wolf, a Democrat who has had a predictably tumultuous relationship with the legislature, and Scarnati is already predicting another budget battle this year.

For the Republican caucus, Crompton says the budget is front and center, with pension reform being most important to the members, but compromise will be in short supply.

“Unfortunately, both in Harrisburg and Washington, it seems people are running from the far left or the far right, and then want to govern (from those fringes),” says Crompton. “That accounts for a lot of the dysfunction we are currently encountering.”

In his telling, Scarnati is a voice of reason who still tries to avoid giving in to the most extreme voices in his party while ruling from the middle — with Crompton pounding the pavement to make sure the president’s voice comes through loud and clear.

Marian Tasco

The kingmaker

When Marian Tasco moved from West Philly to East Mount Airy in 1969, the middle-class neighborhood on the fringe of the city was changing.

“Whites were moving out and blacks were moving in,” she recalls. “And I felt, back in the 1970s, there was very little attention given to African-American neighborhoods. I thought there was more attention paid to (majority white) South Philadelphia or the Northeast – that their services were more of a priority than ours.”

Today, Tasco is one of the most influential figures in city politics, but during this time of social upheaval in Philadelphia, she felt powerless.

With City Hall dominated by white politicians from ethnic neighborhoods, Tasco and a new generation of fellow young political crusaders saw politics as the only venue for black Philadelphia to make its voice heard. In 1975 she joined the mayoral campaign of Charlie Bowser – the first black man in the city’s 300-year history to seek the city’s highest office in a general election.

“I was naive,” she reflects today. “I thought when Charlie ran, the world would change, because we’d have an African-American man running. But that didn’t happen … I learned to be realistic.”

Bowser lost, and Tasco says she learned that righteousness and optimism alone wouldn’t cut it. Real change would take deal-cutting, money and the long, hard work of retail politics – the same formula the white political machine employed to keep its stranglehold on City Hall jobs and services.

Today, 78-year-old Tasco sits in her leafy home, exhausted from another primary. She officially retired from a 32-year political career last spring. But the ward that she still leads, outwardly a fairly ordinary middle-class black community, is the single most influential ward in Philadelphia. And it has made Tasco one of the most powerful retirees in the city, if not the state.

She bucked many established black political leaders by endorsing mayoral contender Jim Kenney, who is white – in turn securing support in white electoral wards for proteges Derek Green and former state Rep. Cherelle Parker in their City Council bids.

That was Tasco the realist in action. The move was hailed by the press as the moment when Kenney, a last-minute candidate, clinched the election. Later, when the Philadelphia Democratic City Committee endorsed indicted Congressman Chaka Fattah, Tasco’s refusal to back the incumbent helped end his 22-year career in Washington, D.C., at the hands of the candidate she wound up supporting, state Rep. Dwight Evans.

“I am very straightforward with Bob” – that would be Congressman Robert Brady, who leads city Democrats – “I tell him, ‘I can do this,’ or ‘No, Bob, I can’t do this,’” she said.

She couldn’t “do” Fattah. And that was that.

“I’m only talking about (Fattah) as a congressman, but he doesn’t pay attention to us up here,” she elaborates. “So, I called him and said, ‘I’m disappointed in the way you neglected us.’”

Other ward bosses might have faced a rebuke from the powerful congressman, but Brady respects Tasco’s power. Fattah garnered 59,000 votes to Evans’ 70,000, with 20,000 votes alone coming from just five wards controlled by Tasco and Evans in Northwest Philadelphia.

And when the party lined up against Democratic Attorney General candidate Josh Shapiro, again Tasco said “no.” She didn’t know Steve Zappala, Shapiro’s Pittsburgh rival.

“Josh came to the ward meeting and made a presentation. He’s not a stranger to us because he’s across the street in Montgomery County,” Tasco said. “We knew him. We knew Katie McGinty, too.”

Shapiro kissed the ring and walked away with 25,000 votes from Tasco and Evans’ allied wards.

Tasco says her success is all about knowing people, many of whom have contributed to her ward committee and a closely allied PAC called Liberty Square. She knows the candidates she wants to support and she knows her neighbors from community meetings, block parties or the grocery aisle. They trust her, so they trust the candidates she likes.

“I don’t look for candidates; I look at them,” she said. “I’m not trying to put anyone out of business. I don’t oppose the city committee just to oppose.”

In other words, it’s not so different from when she got started back in the 1970s.

Some things have changed. For one, Tasco no longer has to worry about whether her neighborhood is a priority in the city hierarchy. Today, if a block is dirty or a rec center needs a swingset patched, she can get it taken care of.

“We had a lot of new neighbors move into this ward. I have about three or four white families in my district, in fact,” she said. “Times are changing; the neighborhood is decent. A lot of people are moving in, so we can’t just sit back.”

Mike Long

The consultant

Mike Long says he understands what the average Pennsylvanian wants because he is one. In his view, it’s what sets Long + Nyquist and Associates, the political consulting firm he founded with Todd Nyquist, apart from its competitors.

“I think the best attribute we bring – both myself and Nyquist – is we’re both working-class guys. My father was a carpenter; Nyquist’s was a lineman. We understand what working-class Pennsylvania is because it’s what we grew up with,” he said. “It’s difficult in our business, because too many lose touch with working people.”

Long, who was born in Lebanon County, where he still lives, got his start in politics as a teenager writing letters to his local newspaper supporting President Richard Nixon and the war effort in Vietnam. After being thrown out of the local Chamber of Commerce for being “too partisan,” Long says he joined the local chapter of the Young Republicans. He rode into Harrisburg as part of the campaign retinue for longshot Speaker of the House candidate H. Jack Seltzer, the Lebanon bologna king, in 1979.

He worked in the statehouse for three decades, eventually joining the staff of state Senate president Robert Jubelirer in 1983. But both wound up jobless in the wake of the 2006 legislative pay raise scandal and “Bonusgate,” in which Long got $41,000 in bonuses spread over two years.

“Everyone knew the pay raise would be poorly received, but the extent of the pay raise scandal surprised everyone in the legislature,” he recalls. “But I still wanted to continue to be involved in both sides of politics.”

Long went on to partner with Nyquist, advising elected officials and campaigning for new Republican candidates. They found success in flipping Western Pennsylvania districts where working-class Democrats, drawn into the party by unions, felt increasingly disconnected from the state party’s politics on gun rights and abortion.

“Western (Pennsylvania) has really dramatically changed,” Long explains. “There’s a lot of reporting about Southeastern (Pennsylvania) going Democrat, but less about the Southwest Republican change. We’ve had a terrific string of victories and we’ve got a great box score. We’ve been involved in replacing nine Democrats with Republicans.”

He credited his success to selectivity, saying his firm has turned down several low-grade candidates, and to opponents underestimating what he calls the “diversity” of the Keystone State.

“I once ran a race in Montgomery County, and my clients asked me how it compared to Republican races in Northern (Pennsylvania). I said, ‘Every single position is the opposite,’” Long recalls. “They think their views will play everywhere that they don’t. For example, the severance tax for natural gas. Folks in Southeastern (Pennsylvania) are for that in large majority, but in the Northern Tier, they benefit from it. Someone running statewide just has to understand that.”

Today, his firm is repping John Rafferty in his run for attorney general, Otto Voit’s campaign for state treasurer and John Brown’s for state auditor general (all Republicans, of course), along with dozens of lobbying contracts.

Long describes himself as a “Reagan Republican,” who ascribes to the former president’s “big tent” philosophy of welcoming conservatives of all stripes. Interestingly, the shifting nature of rural conservatism that brought Long success has continued to change, and the consultant said he worried about the drift away from traditional economic conservatism – think Trump – and toward a party dominated by a quest for ideological purity.

He says these shifts were harming public perception of government and making it harder for good candidates to jump into politics.

“Todd and I went to a district about four years ago trying to recruit a candidate” he remembers. “He was a local businessman and he said to us, ‘You want me to spend three nights a week in Harrisburg for less money than I’m making now, so I can get criticized for the positions I take while most people think I’m some crook?’ Honestly, it was kind of hard to dispute his argument.”

Walter D’Alessio

The builder

There are two Walter D’Alessios.

One version exists on paper. He’s a guy from a chicken farm in Western Pennsylvania who holds a degree in landscape architecture from Penn State. He ran the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority in the 1970s and also happens to sit on a number of many strangely prominent boards in the city, from PECO to Independence Blue Cross to Brandywine Realty Trust.

Eighty years old, he lives in Roxborough and today operates a small mortgage firm, NorthMarq Investments, out of an office on Market Street. A sheet of paper with his company’s name scrawled in black marker is taped to a door that points the way down a narrow hallway that leads to NorthMarq.

“We’re a small firm with a small number of clients – and we like it that way,” he says of the company.

This is a technically accurate summary of the bureaucrat-turned-mortgage broker’s life. But it is a summary that ignores the other Walter D’Alessio – confidant to half a dozen Philadelphia mayors, untold city council members, and some of the city’s most prominent businessmen.

This is D’Alessio the builder.

When former Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo was struggling to lock down billions in federal funding for a submerged train line that would link the Penn and Reading railroads downtown, he called D’Alessio.

“I called the federal secretary of transportation – and he understood the importance of the project because he was a Philadelphian – but he said, ‘You have to get an equal amount of private investment. I need an office building,’” he recalls.

So, D’Alessio made it happen by securing tenants, signing Aramark and the city’s water department onto leases that underpinned the construction of a tower that today bears the food purveyor’s name. Federal funding flowed into the rail tunnel project, uniting the region’s rail system.

Many of the city’s biggest developments seem to trace back to D’Alessio in this quiet way. As a member of Brandywine’s board, he convinced a suburban Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust to double down on a modest office tower proposal near 30th Street Station, which has ultimately become today’s trio of Cira Centre buildings. On the board of the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation, D’Alessio helped push the shuttered Navy Yard toward its current iteration as a booming office park, and counseled Montgomery County Commissioner Josh Shapiro to consolidate county jobs in Norristown to spur development in the beleaguered county seat. The stadiums, the Pennsylvania Convention Center, I-95: D’Alessio was there for all of them.

Thirty years after the Aramark deal, when longtime Aramark CEO Joe Neubauer retired, he called D’Alessio to warn that his successor, Eric Foss, would try to move the company out of the city. After an experiment with shipping a unit of Aramark to Nashville that D’Alessio described as a “fortunate disaster,” the mortgage broker from Roxborough and a string of city officials met with Foss and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

“Their people didn’t want to move – the ones that did came back,” D’Alessio said. “(Foss) kept complaining about the environment, people on the street, the methadone clinic nearby. We got the city to clean up as much as they could and then we started to do everything we could, all the incentives we could, to get them to move to a new building.”

The company decided to stay, and will be moving to a new tower in Center City when its current lease expires in 2018, likely with city-provided tax breaks. D’Alessio thinks Thomas Jefferson University, spilling out of a collection of cramped buildings downtown, would be perfect to backfill Aramark’s old space.

This is how D’Alessio talks about Philadelphia, as though the Class A office towers and Fortune 500 companies were game pieces being repositioned on a chessboard. D’Alessio is central to many important things in Philadelphia, but, in keeping with his persona, he doesn’t take credit for any of them.

D’Alessio’s real skill, to hear him tell it, is building relationships and bringing people together. He can do this because of his background, but also because of his power to make other people see Philadelphia in the relentlessly positive way that only an urban convert from the hinterlands could.

“Once something gets built, you can have a dedication or a ribbon-cutting and you can put the people on that platform who can help you get the next project done,” he explains. “The only value I bring to this stuff is that I know some of the steps. My view, by and large, is that politicians want to do the right thing. My job is to help them see the right thing.”

A gentle man with a face that seems to be permanently beaming, D’Alessio may be a living embodiment of soft power, perpetually cajoling politicians – although his Keystone Alliance PAC certainly helps pols to see the light.

Like his Chamber of Commerce board colleague William Sasso, D’Alessio views tamping down dysfunction in Harrisburg as his next project.

“Gov. (Tom) Wolf is an interesting guy, but he’s isolated himself – even in the toughest periods of time, where we had fights, after the big one, some of us would go around to get whatever we wanted done. That’s not happening now,” D’Alessio opines. “We might have another one-term governor.”

Daisy Cruz

The organizer

Five years ago, the notion of a $15 minimum wage was, at best, a radical idea that would draw scoffs from Republicans and Democrats alike.

Today, with crowds of frustrated fast-food workers banging down the doors to Philadelphia’s City Hall or the statehouse, a lot fewer people are laughing. Daisy Cruz, from the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), can turn out 10,000 members across the Philadelphia region.

The union represents janitors, security guards and other service-sector workers who are employed in skyscrapers and office parks from Wilmington to Bethlehem. Although her movement hasn’t found a way around Pennsylvania’s preemption law, the $15 demand has been weaponized by the union in its contract negotiations in both the Southwestern and Southeastern regions of the state.

“We might not always win the whole thing,” Cruz says in her purple-bedecked offices on Market Street – right across from Philadelphia’s City Hall. But the $15 demand allows her members “to go to the bargaining table and fight for that.”

“We have to continue, because even these small pockets (of unionized workers) actually help the larger fight,” she says.

As the Mid-Atlantic director of SEIU’s 32BJ – a mega-local that stretches from Florida to Boston – Cruz is on the front lines of the daylong mini-strikes, traffic-clogging Market Street rallies and pickets at the airport that Philly-area residents have been experiencing the last couple years.

Cruz grew up at Fourth and Indiana streets, in an area of Kensington that became known as “The Badlands” after former Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Steve Lopez penned “Third and Indiana,” a gritty novel about the crime-plagued area, in 1994. Much of her family still lives in the neighborhood, and Cruz still attends church there, although she has since decamped to Mayfair in the northeast.

She started working for SEIU in 1998, when the local union realized that while its membership was increasingly Hispanic, it had no Spanish speakers on staff. Since then, Cruz has worked her way up from a receptionist to assistant area leader and, three years ago, to district leader – just as the Fight for $15 movement was taking off.

Now she is at the helm of a union whose scope stretches from Delaware to the Lehigh Valley.

“My priority is to continue to raise their wages and continue to keep these good jobs, especially when they are cleaning and maintaining and securing these beautiful skyscrapers,” Cruz says.

Asked how her union, which is majority Hispanic and African-American, interplays with the predominantly white local building trades unions (which sometimes employ anti-immigrant rhetoric), she simply offers: “If a building should be built by hardworking people paid a living wage, once it is done, whoever is maintaining that building should also be paid a living wage.”

32BJ maintains a powerful get-out-the-vote apparatus, which includes three political clubs: in West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia and in the River Wards neighborhoods. From these locations, members come together to eat meals, learn about the candidates and canvass their respective neighborhoods in favor of whichever politicians meet their specifications.

In the past year, Cruz and her union have orchestrated a series of eye-catching – and car-stopping – rallies and protests for the $15 minimum wage in a parallel effort to the socialist “$15 Now” group, which often has more radical demands. Stymied at the city and state level for now, SEIU has been using the demand for $15 as a cudgel in contract negotiations with building operators in its three different master contracts with employers in Philadelphia, its suburbs and in Delaware.

During the rallies in support of pay raises and preserved benefits, a who’s who of Philadelphia’s powerful politicians, from Mayor Jim Kenney to Darrell Clarke, spoke in support of the workers. Although strike votes were taken and authorized last year, the employers caved before the workers walked out.

As long as Cruz has the clout to summon similar numbers of protesters and political support, she’ll likely enjoy similar results.

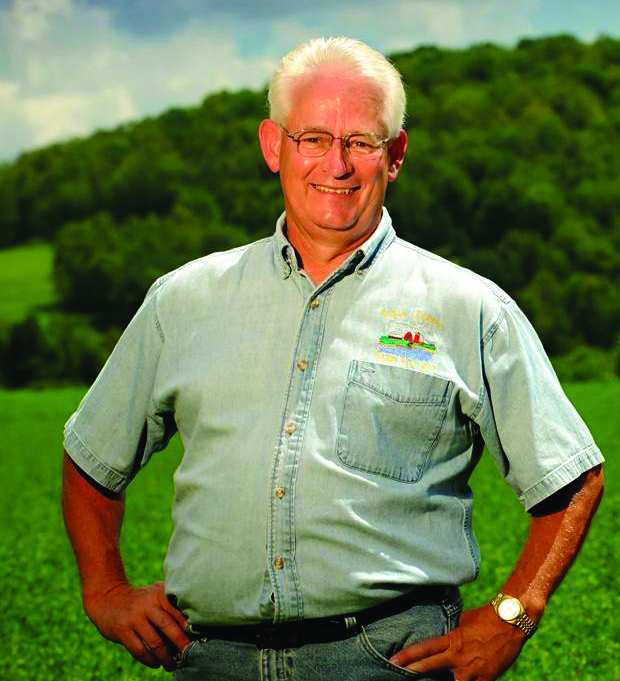

Erick Coolidge

The farmer

Erick Coolidge is a lifelong dairy farmer, a Tioga County commissioner – and one of the Northern Tier’s preeminent political leaders. He speaks fondly, and often, of awakening at 4 a.m. to milk the cows before donning his suit to head into the county seat of Wellsboro (which, at almost 3,300 residents, is the second-largest municipality in the county).

First elected in 1995, the 62-year-old Coolidge decided to seek another term in 2015 after publicly considering retiring from politics. Part of his regional influence can be chalked up to the longevity of his reign: Coolidge has cultivated relationships across Pennsylvania – including with politicians like state Senate President Joe Scarnati – and a lifetime spent among the people who became his constituents has provided him with an intimate understanding of the inner political and economic workings of this part of the state.

In addition to his role as one of the county’s three commissioners, Coolidge actively exports his expertise. He ensures that his region’s voice is heard by sitting on a multiplicity of commissions and boards, including the National Association of Counties, the Mid-Atlantic Dairy Association, the governor’s Conservation and Natural Resources Advisory Council and the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania.

“We oftentimes are not the first on everyone’s agenda because the size of the population doesn’t really warrant the amount of attention” received by populous suburban and urban areas, says Coolidge. “It’s a delicate position. The rural areas oftentimes do not have as strong a voice as the metropolitan areas. But one size does not fit all, and we may have to modify (state policy) a bit to make sure we don’t alienate the rural section of the population.”

One high-profile area where Coolidge wielded his influence is in the taxation and regulation of the natural gas industries. When well pads and drills started operating in earnest throughout the northeastern part of the state at the end of the last decade, he was a leading voice arguing that the companies should pay an impact fee to compensate host regions for the environmental, social and infrastructural burdens brought by the industry.

In 2012, Coolidge and his allies in the County Commissioners Association successfully encouraged Gov. Tom Corbett to pass Act 13, which gives counties and localities the power to assess an impact fee for each gas well – which can only be spent within their boundaries.

For Tioga County, that meant over $16 million in new infrastructure investments, including an emergency services center, a new hangar at the airport and upgrades to the prison and courthouse. Today, Coolidge calls it “perhaps one of the best pieces of legislation to be created for this specific issue and need.”

Coolidge is known as a serious and civil politician. Although he is based in a very conservative region, he isn’t known as a partisan street fighter or a tea party ideologue. Instead, he acts as an elder statesman for Northern Tier Republicans, although he would be loath to describe himself that way.

Coolidge’s name may not ring out in Harrisburg, but statewide power has never been a priority for him. He has other matters to attend to, after all. His 700-acre, 173-year-old dairy farm, Le-Ma-Re, was named a “Dairy of Distinction” in 1990. Keeping it that way, in Coolidge’s telling, is his first priority.

Ryan Boyer

The Laborer

Ryan Boyer’s star is on the rise. The North Philadelphia native became a member of Laborers Council 332 during his summers home from college, where he worked for construction contractors. Over 20 years later, Boyer, 45, heads up the Laborers' District Council of the Metropolitan Area of Philadelphia and Vicinity. His almost 6,000 members live in all five counties of Southeastern Pennsylvania.

“The unofficial job is to get the next job – whatever it takes to bring commerce into this region, I’ll do,” says Boyer. “Politics is about as important (to the work I do) as oxygen is to breathing. It makes me chuckle when people say they aren’t involved in politics. Politics is involved in our business, so you’d better be involved in it. (Politicians) have the resources, they have awesome powers of zoning and land use. You have to be involved in politics to ensure there is a level playing field.”

Philadelphia’s building trades unions have a reputation for being vastly majority white, suburban-oriented and intimately involved in the politics of the city. The Laborers are different in the first two capacities (Boyer estimates that 60 percent of members live in Philly), but the union is just as engaged as its counterparts in the Carpenters, Steamfitters or Electricians Local 98, the undisputed heavyweight of the local labor movement.

Boyer’s power in the city and the region is likely to continue to grow. The Laborers backed a dud in the 2015 mayoral election, throwing their support behind early favorite Anthony Williams, but their bets this year have proved better.

He is a close ally of state Rep. Dwight Evans, a leader of the Northwest Coalition that represents a series of high-turnout, middle-class African-American wards near the border of Montgomery County. The Laborers supported Evans in his successful primary challenge to incumbent U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah.

Boyer also supported Montgomery County’s Josh Shapiro in the heated Democratic attorney general primary, despite most other Philadelphia building trades unions backing Allegheny County’s Stephen Zappala. Boyer and his members also backed a host of other primary winners, many of them Democratic party favorites like Sharif Street, son of former Mayor John Street.

“Laborers District Council is the No. 1 funder of African-American candidates in the state of Pennsylvania, period,” Boyer says when asked about his union’s place in the Philadelphia building trades-oriented labor movement. “The numbers say that, not me. My guys work really hard to have a profile and sometimes, quite frankly, it pisses me off that we’re ignored. I don’t know why that is, but we’re out here. You ask politicians about the people who helped them and they’ll tell you.”

Even the 2015 mayor’s race didn’t end badly for the Laborers. Evans was a major player in Jim Kenney’s victory in the Philadelphia mayor’s race, and Boyer is a fan of the new mayor.

Last year, Boyer’s strength grew when Gov. Tom Wolf appointed him chairman of the Delaware River Port Authority, which operates the Benjamin Franklin Bridge and the PATCO regional rail service.

Although the DRPA, co-operated by Pennsylvania and New Jersey, has long had a reputation for opacity and corruption, Boyer says he is continuing the legislative-ordered reforms begun in 2011, and is seeking a contract for the agency’s union employees who have been working without one for much of New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie’s tenure.

But there are regional – and partisan – limits to Boyer’s influence. His district council only encompasses the Philadelphia metropolitan area and, as state politics become ever more polarized, the influence of labor leaders is increasingly relegated to Democratic strongholds.

Boyer insists on his union’s bipartisan credentials, and Republicans in Delaware County boast of their good relationships with him. But the number of sympathetic Republicans grows ever smaller, even in Philadelphia’s blue-collar counties, as ideological and partisan differences sharpen. The only Republican politician Boyer mentions by name as an ally is Dominic Pileggi, the former Delaware County state senator who lost his position as majority leader because he was deemed too moderate.

Michael Puppio

The champion of Delco

Michael Puppio’s offices sit on a quiet, tree-lined street in Media, the seat of Delaware County. He’s a partner in the law firm Raffaele Puppio, which serves as a solicitor for school districts and municipalities. It’s the kind of work that requires an encyclopedic knowledge of the inner workings of the second-most densely populated county in Pennsylvania.

Good thing Puppio’s sideline work is in politics, which he describes as a “hobby,” but which, from the outside, looks like a second full-time job. And even in this age of increasingly nationalized politics, it’s the local races that get him excited.

“You are drawn into politics by national issues,” says Puppio. “Then, as you get more involved, it’s the recognition that it’s local politics that influences most of what happens to us day-to-day.”

Puppio, 49, was born, raised and still lives in Springfield, a prosperous suburb with a median income of about $90,000. Located just west of Upper Darby, it has long been a potent stronghold of the county’s Republican organization. It has yet to be affected by the demographic changes sweeping the townships on its eastern borders, which have become more racially and politically diverse as immigrants and African-Americans from West Philadelphia have moved in.

During the second half of the 20th century, the Puppio family ran the largest banquet hall in the county, where many of the great political fêtes were held when the Delaware County Republican Party was the most slickly oiled political machine in Pennsylvania. Puppio dates his interest in politics back to those galas, and when he returned to Springfield after law school, he jumped into local party politics.

Puppio eventually became a commissioner for the township and a county councilman. But these days, he is more of a behind-the-scenes actor, serving as chairman of the Springfield Republican Party and as chairman for numerous political campaigns. From those positions, Puppio keeps a keen eye out for young party recruits – a hugely important skill for local party building.

“You have to try to do it because there aren’t people knocking at your door saying, ‘I want to be involved in my local party,’” says Puppio. Asked whether he would ever run for office, he responds: “I’m not interested. I want to play a role in selecting and advocating for a candidate who can carry forward Republican principles.”

Puppio first chaired former Congressman Curt Weldon’s ill-fated re-election campaign in 2006, which he lost to Joe Sestak. But he recruited many interns and low-level campaign workers from that campaign for the county GOP: Nick Miccarelli, now a state representative; Caitlin Ganley, now political director for Congressman Pat Meehan; Meredith Buettner, Meehan’s finance director; and Alex Charlton, who is chief of staff to state Sen. Tom McGarrigle and a candidate for the 165th District Pennsylvania House seat. In recent years, Puppio has continued to find fresh recruits and backed winning candidates, including McGarrigle and Meehan.

Puppio is well known in Harrisburg as well. After Delaware County state Sen. Dominic Pileggi lost his post as Republican majority leader in 2014, Puppio ensured that the region would still have a connection to the state Capitol by building strong ties to Senate President Joseph Scarnati’s office.

Nonetheless, Puppio understands that he is in a tricky position. Meehan faced a primary challenge from a tea party conservative this season, further evidence that the Delaware County Republican party – which counts both centrist voters and organized labor among its constituencies – appears out of sync with the increasingly rigid ideology of the larger party.

On the other hand, the Democrats are trying to press their advantage in the eastern parts of the county, where they court Philly expats, immigrants and moderate voters hesitant to split their vote between national-level Democrats and local-level Republicans. Similar dynamics have already humbled the Montgomery County Republican Party, which lost nearly every local election in 2015.

“The national trend has been that you get less ticket-splitting, but I would say this is an area that bucks that trend,” says Puppio. The 2014 election results would seem to confirm that: Gov. Tom Wolf won Delaware County by almost 40,000 votes, but McGarrigle beat his Democratic opponent by 4,000 votes.

“We don’t buck that trend for any other reason than folks working it,” says Puppio. “On the national level, could that wave come? Absolutely, it could. That’s why I lay awake at night looking at the ceiling, trying to figure out whether I have done everything that I could to provide guidance for the campaigns I’m working on.”

Roger Richards

The captain of Erie

Roger Richards has been involved in Pennsylvania politics since the 1960s, when the state, Harrisburg and the Republican Party all looked very, very different. But no matter how much state politics have changed, this old-school lawyer from Erie, who is also vice-president of the Pennsylvania Society, is still making things happen.

Richards, 70, has been a player for decades, raising money for mostly Republican candidates while championing economic development projects in and around Erie. Despite the high-profile nature of his avocation, Richards prefers to remain behind the scenes.

“I’m a little apprehensive about this – that’s been my goal, to avoid publicity,” he says during an interview. Later, when asked about his priorities for the coming year, he laughs. “Well, I’m trying to avoid publicity; that’s one priority. I don’t think you’ll get your 600 words from this conversation.”

Richards was a teenager when he started out in politics as a page in the state Senate. He recalls mid-century Harrisburg as a place of greater comity both within and between the parties.

Although he isn’t a fan of the seemingly ever-increasing polarization of today, Richards also hesitates to say that the arrangements of the past were better. Party bosses used to run the show, and he doesn’t miss their influence.

Richards is certainly a strong Republican, but his first alliance is to his region. Erie – both the county and city – are rare Democratic strongholds in northwestern Pennsylvania, and he has friends on both sides of the aisle on his home turf.

“What I like to do is organize our general assembly delegation from our area to be united when we look for certain things to be supported in northwestern (Pennsylvania),” says Richards. “Erie is the farthest community from the state capital, and without a lot of electronic or print media to get our message across. To make a presentation to decision-makers, you have to be more organized when you come from this part of the state.”

Richards has focused much of his attention on Presque Isle Bay, one of Erie’s principal attractions, and was a key player in making the almost 29,000-square foot Bayfront Convention Center a reality. In addition to that institution, which opened in 2007, he was instrumental in bringing an estimated $200 million in economic development, with help from the state, to the city’s post-industrial waterfront.

Considering his longstanding political ties, Richards’ job is no doubt made easier when the governor is a Republican – not because he has bad blood with state-level Democrats, but because his ties to the GOP have been much closer.

Richards enjoyed very good relations with Tom Corbett when he was governor, but he was closest with fellow Erie denizen and former Governor Tom Ridge. “Tom Ridge did ask me to support Jeb Bush, and I did financially, and then Marco Rubio,” Richards notes when asked about his recent political involvement.

It isn’t as though Harrisburg is closed to him with Tom Wolf in office, but Richards has no desire to talk with a journalist about what he’s working on in the capitol or elsewhere in the political arena.

“People in Harrisburg know what (my priorities) are, and I don’t really believe in publicizing those efforts,” Richards says. Nor does he care to detail his political fundraising efforts. “I try to raise funds through various committees because people always try to track the source of funds. Well, I just don’t like to get my name out front on anything for either party. Am I supporting people financially? Yes, but I’m doing it in ways that probably no one would be able to figure out.”

One to grow on:

Julie Hallinan

The captain of Erie

Julie Hallinan has mostly been profiled in the past for her youth – PoliticsPA noted the promising young Pittsburgh-based fundraiser in 2014 after Tom Wolf’s gubernatorial campaign picked her up.

Two years later, there’s another, more relevant number associated with the 25-year-old Hallinan: $1.2 million.

That’s roughly how much she has helped Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald raise since joining his campaign last year. And to be clear, Fitzgerald faces no challenger for his seat.

“The county executive is very involved in supporting down-ballot candidates,” Hallinan explains. “It’s about continuing to grow the impact and being able to benefit constituents across the commonwealth, so we can expand not just here in Allegheny County. It’s something he and I feel very strongly about.”

Hallinan and Fitzgerald’s impact in Allegheny County has largely revolved around marginalizing the influence of the so-called “Network” – a collection of businessmen and political operatives aligned with former Pittsburgh Mayor Luke Ravenstahl that had a lock on political fundraising and influence in the Steel City for nearly a decade.

No longer. Since Fitzgerald moved from city council to county executive in 2011, he has scored a string of wins: Bill Peduto’s successful Pittsburgh mayoral campaign and several council races featuring similar candidates were all backed by Fitzgerald, who has always been a capable fundraiser. Hallinan has helped him and his growing cadre of allies raise even more money since coming on board at the beginning of 2015.

“We raised about $600,000 just in November and December last year,” she says.

Hallinan hails from what she describes as a “civically engaged” family in Altoona, the town she left to study political science at the University of Pittsburgh. She fell in love with the city’s Shadyside neighborhood and fast-paced campaign life after an internship at Sen. Bob Casey Jr.’s Pittsburgh campaign office in 2012. She hopped on Allyson Schwartz’s failed gubernatorial primary bid and then over to Wolf’s successful campaign in the general election.

There, she met Eric Hagarty, Fitzgerald’s former finance director who became Wolf’s deputy campaign manager. Hagarty was impressed enough with her abilities to recommend her for his old job in Allegheny County.

Hallinan credits her rapid ascent in Pittsburgh-area politics to Hagarty’s assistance and mentorship from Grant Forbes Managing Partner Mike Butler and Aubrey Montgomery, principal at Rittenhouse Partners – along with her own abilities.

“I’m sort of a jack-of-all trades,” she said. “It’s about being flexible, but also organized – I’m one of the most organized people you’ll ever meet.”

The allure of ready campaign cash has helped Fitzgerald consolidate even more power around the state’s western metropolis. An attempt to replace county controller Chelsa Wagner with another Fitzgerald ally hit a wall last year. But this year, Hallinan helped organize a joint fundraiser with Wagner.

“They were listed on the fundraiser invitation together,” Hallinan recalls. “It was a tough primary, and afterward, they took time to sit down and try to make amends a little bit. They realized this was something that the public was unhappy about, so the relationship has been mended and is much healthier. It was something that we all agreed on.”

She started work on Katie McGinty’s Senate campaign in February. Her next priority is ensuring Peduto enjoys a well-funded mayoral reelection campaign next year.

NEXT STORY: Mayor says liquor tax is already tapped