Elections (Archived)

El-Shabazz was disciplined, removed from cases as a defense attorney

Tariq El-Shabazz at the press conference announcing his candidacy for Philadelphia District Attorney

Until his retirement in 1999, Philadelphia police detective Brian Grevious spent his career putting criminals behind bars. But he’s devoted a significant chunk of the ensuing 18 years trying to get one man, Anthony Brown, out of jail.

Grevious believes Brown was wrongfully convicted of a 1998 homicide simply because his defense attorney failed to look into his alibi.

“This kid should not be in jail,” Grevious told City&State PA. “His lawyer just didn’t do any investigation on a capital murder case.”

That lawyer: Tariq El-Shabazz, now a candidate for Philadelphia District Attorney.

Brown, who is serving out a life sentence at a state prison three hours west of Philadelphia, puts his situation simply.

“Tariq El-Shabazz violated my right to a fair trial for a crime I did not commit,” he wrote in an email.

There is no shortage of incarcerated individuals eager to pin their troubles on their defense lawyers. But after 17 years of appeals, two federal judges have agreed that El-Shabazz did fail to adequately represent Brown – and a City&State PA investigation found that this wasn’t an isolated incident.

A string of incarcerated men told similar stories: that El-Shabazz took their cases and their money, then seemed to vanish. Court records show that the defense attorney missed court dates and, in some cases, misstated facts to judges to excuse his absences. Some of El-Shabazz’s former colleagues have said his conduct later contributed to his well-documented money problems as his reputation deteriorated.

In Brown’s case, Grevious said El-Shabazz hired him to investigate the young man’s alibi just days before the 26-year-old went to trial in 2000 – two years after he took the case.

“El-Shabazz hired me, I think, on a Friday. So, I asked, ‘When’s the trial for this?’ And he said, ‘Tuesday,’” recalled Grevious.

The ex-cop located two witnesses who had waited on Brown at a restaurant across town around the time of the fatal shooting of which he would be accused. But – through no fault of his own – Grevious was too late to have them testify in court.

“El-Shabazz billed Brown’s family $25,000 upfront in 1998 and then didn’t do any investigation for two years,” he said, his frustration and anger over the incident still evident.

A legal expert agreed that El-Shabazz’s conduct in the case was inexcusable.

“Anyone can make a mistake, but this is a clear-cut failure to investigate and present an alibi defense,” said Temple law professor Louis Natali, a former colleague of El-Shabazz who reviewed Brown’s case. “It amounts to ineffective assistance of counsel and should result in appropriate relief granted to this defendant, who may be innocent.”

But with his appeals exhausted, Brown’s best hope is for the District Attorney’s Office to review the conviction. In a bizarre twist of fate, that office’s Conviction Integrity Unit was most recently overseen by El-Shabazz himself and staffed by Assistant District Attorney Mark Gilson – the same man who put Brown in jail for murder.

In his campaign for DA, El-Shabazz has blasted the media for focusing on his money troubles instead of the compassion for vulnerable men the former defense lawyer brought to the District Attorney’s Office. But Grevious, who has worked with Brown’s family for years on their son’s appeals, claims that neither El-Shabazz nor Gilson were ever interested in reviewing the case.

“(El-Shabazz) is the gatekeeper for the cases they drop charges on. I’m reading in the paper about two or three people who actually did shit that were released due to ineffective counsel,” he said. “But he never looked at his own case. He made sure Anthony Brown’s ass stayed in jail.”

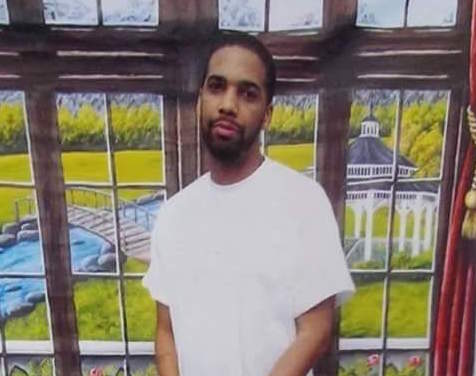

A photo of Anthony Brown in Graterford prison - photo provided by Brown family

During the humid twilight hours of Labor Day 1998, the Rorie family was cleaning up after an afternoon block party on narrow Conestoga Street in West Philadelphia. Around 8:15 p.m., a gray car rounded the corner and screeched to a halt.

Four men jumped out, brandishing pistols and automatic weapons. One man aimed a gun above his head and fired into the air.

The pop of gunfire sent neighbors scattering across porches and vacant lots. But Frances Rorie, the matriarch of the family, was caught in the middle of the street. As she struggled to squeeze between parked cars, a second man leveled an Uzi in her direction and fired.

A police report states that of the 17 rounds discharged, 16 impacted harmlessly on the sides of rowhomes. But a single shot coursed through Rorie’s skull, killing the 51-year-old instantly. The murder was called in shortly afterward, around 8:25 p.m.

The shooting took an instant, but the events leading up to Rorie’s slaying and to murder charges being brought against Brown began hours earlier, as a teenage Hatfield-and-McCoy drama played out on the block. Teens from Conestoga Street and from a nearby block of Girard Avenue had feuded throughout the day’s festivities. There were verbal altercations, rocks thrown, knives brandished, threats of retribution made.

The victim’s 12-year-old granddaughter, Tamika Thompson, and Thompson’s aunt, Yvonne Rorie, had feuded with Brown’s sister, whose family lived on the rival block. The pair would later finger Anthony Brown as the shooter, stating they had seen him with friends, ominously pointing at the Rorie household earlier in the day. Police recovered clothing matching their description from Brown’s home: a white tee, jeans and an Atlanta Braves hat. Brown owned a gray car and had used an alias and fake address during an unrelated traffic stop hours before the shooting, which damaged his credibility.

But as far as capital murder cases go, it was hardly a slam dunk – one appeals judge would later comment that “evidence of guilt was hardly overwhelming.” Yvonne Rorie and Thompson, whose testimony would help doom Brown, had feuded with his sister. Two other relatives of the victim would contradict the pair’s description of the shooter when interviewed by police. No murder weapon was ever recovered, and Brown had no criminal record.

Most importantly, Brown had an alibi: He was eating dinner at a TGI Fridays three miles away with friends at the time of the shooting.

District Attorney Lynne Abraham’s office nevertheless ran with the witnesses’ version of events, issuing a warrant for Brown’s arrest. ADA Gilson argued Brown’s motive was to avenge his sister’s honor after she had squabbled with Rorie family members. Brown surrendered a few days after the shooting.

Brown’s father, Arthur Boyer, was so confident in his son’s innocence he scraped together the money for a high-priced private defense attorney – no small feat for a postal worker. El-Shabazz was a rising star at the time and Boyer forked over thousands of dollars for a retainer fee.

Boyer explained his son’s alibi, describing a waitress and restaurant manager who had talked to Brown the night of the shooting, not to mention possible security footage, receipts and other exculpatory evidence.

“He said, ‘We’re going with the alibi defense,’” Boyer recalls El-Shabazz assuring him.

But as the months leading up to Brown’s trial turned into a year, the young man would tell his father that he’d barely heard from his crack defense lawyer.

“He came to see me one time in the two years that I waited to go to trial,” Brown says today.

At one point, Boyer was contacted by a “shifty” private investigator named Billy Padden who said he was working for El-Shabazz. The man peppered him with basic questions about the case: Where was Anthony that night? Who was he with? Did anyone else see him?

Boyer was alarmed – how could the man investigating his son’s alibi not know the first thing about it?

“I probably called (El-Shabazz) 10 times before the trial. He always just said, ‘Everything is under control,’” Boyer recalled.

In reality, though, the investigation was dead in the water. El-Shabazz got into a dispute over payment with Padden and the PI disappeared, along with a case file of dubious value.

Little else would happen for Brown until the week before his case went before a judge – nearly two years after Rorie’s slaying – when El-Shabazz abruptly called Brian Grevious, whom he remembered from his time on the force. When Grevious heard the trial date was just days away, he was stunned – and skeptical.

“I immediately went up to the prison and interviewed the client,” he recalled. “I’ve interviewed a lot of people as a detective; you learn when you have conversations whether people are embellishing things. But everything this kid said had the appearance of being truthful.”

Grevious began a frantic search for the restaurant staffers, the only disinterested witnesses who could speak to Brown’s whereabouts. Through calls and a subpoena sent to TGI Fridays’ corporate headquarters in Texas, he would eventually track down Stacy Szmyt, Brown’s waitress, and Andre Osborne, the manager on call that night. Both, miraculously, still remembered Brown and his friends two years after the fact, because, according to court records, “they were loud and because (Osborne) suspected they might not pay their bill.” Both recalled that the young man had left sometime after sundown, which called prosecutors’ timeline for the evening murder into question.

Grevious thought he had broken the DA’s case open when, in fact, the game was already over: Three weeks into the trial, El-Shabazz had already blown a deadline for the introduction of an alibi petition notifying prosecutors about defense witnesses who would testify at trial. The only alibi witnesses El-Shabazz had put on the stand so far were Brown’s friends and relatives – interested parties with sometimes inconsistent stories.

When Grevious hauled the surprise witnesses into court, Gilson and El-Shabazz broke into a heated argument over their inclusion in the trial. Ultimately, the presiding judge ruled that they would not be allowed to testify.

“I said, ‘Why not ask for a mistrial?’” Grevious recalled. “(El-Shabazz) said, ‘No, I’m going to win this.’”

But the lawyer’s courtroom bravado wasn’t enough. Boyer watched helplessly as his son’s defense crumbled and he was convicted of murder.

“I was just baffled. How could this happen after all this time?” he says today. “From day one, he knew about these witnesses. I had told (El-Shabazz) about them myself.”

Boyer estimates he paid El-Shabazz around $13,000 in installments before he realized the lawyer had failed his son. He stopped paying and said El-Shabazz, perhaps to the lawyer’s credit, never sought the rest of his fee.

“My son had never been arrested before,” Boyer said in a recent interview. “I felt like a private attorney would do a better job defending him. Now I know better.”

With nothing but the rest of his life in prison ahead of him, Brown began to file state and federal court petitions largely centering around El-Shabazz’s failure to investigate his case. It would take until 2009 for one such petition, with the eventual help of new lawyers, to make its way to federal judge Arnold C. Rapoport.

According to court records, El-Shabazz was subpoenaed over his work on the Brown case and attempted to skip a date for an evidentiary hearing. But he would be admonished by Rapoport and ultimately forced to take the stand over his work on the case.

He denied allegations that he had failed to investigate the young man’s alibi and that he had failed to pay Padden, the first private investigator he’d hired. But El-Shabazz couldn’t explain why he hired a second investigator only days before the trial began.

He would also state – falsely, as the court would find – that he had filed an alibi notice. When confronted with records showing no notice filed, El-Shabazz seems to speculate that court records might be incomplete.

“The evidence is what the evidence is, there was none found,” he says. “Is that in the record? Absolutely. If it's a complete record, absolutely not.”

The judge was unpersuaded. He found in Brown’s favor, adding that El-Shabazz had also failed to instruct jurors about conflicting eyewitness descriptions of the shooter. As the petition made its way through federal appeals, District Court Judge Louis Pollak agreed that the lawyer’s conduct had contributed to Brown’s conviction.

“Shabazz should have been aware that there might be disinterested alibi witnesses and should, therefore, have investigated that possibility,” Pollak wrote, in a 2010 decision. “Disinterested witnesses corroborating (Brown’s) alibi could weigh heavily in the jury’s decision.”

Veteran defense lawyer William DeStefano said that, in general, for allegations of any defense lawyer’s incompetence to reach a federal district court is an extraordinary occurrence. He acknowledged that while the defense field can be stressful, there are still minimum standards of conduct any lawyer must uphold.

“Generally, the only way to make any living as a defense lawyer is to take a high volume of cases. It’s about stretching yourself – and sometimes these guys get stretched a little thin,” he said. “But it’s no excuse for doing something like ignoring the possibility of an alibi witness.”

Brown’s ultimate goal – a new trial – would remain elusive. The bar for retrying a murder case is high. A final decision by the federal circuit court would call El-Shabazz “deficient,” but because Osborne couldn’t remember precisely when Brown had left the TGI Fridays – only that it was “dark” – Brown could have theoretically raced across town in time to murder Rorie.

Brown is still in jail, his avenues for appeal exhausted. He turned 43 in April.

Word of El-Shabazz’s campaign for DA has spread to Philadelphia’s Graterford prison, a place where a number of his former clients now reside. In interviews, several men in that correctional facility told stories with similarities to Brown’s case.

Daniel Marsh was arrested for robbery, murder and a string of other charges in 1984 and sentenced to life in prison. He’s maintained for decades that two police officers involved in his case were corrupt – both would be investigated (and cleared) over misconduct allegations in a separate case years later, according to a Courier-Post article. Nevertheless, in 2003, Marsh retained El-Shabazz to handle his appeal hearings.

“He lied to me for two years,” Marsh wrote City&State PA from prison. “He said that he would file a brief...but the DA’s office told me that he never filed a brief. Nor did he show up (to court).”

According to court dockets, a judge would ultimately take the unusual step of removing El-Shabazz from that case – a move often interpreted as a sign that a judge lacks confidence in an attorney’s ability to adequately represent their client.

Donald Steward was convicted of rape in 2003. His family paid El-Shabazz to handle his appeal, but Steward, echoing the experiences of Brown and Marsh, also said that the lawyer “abandoned him.”

“He took $8,000 from me,” Steward wrote. “He never gave me my money back.”

Once again, court records show El-Shabazz was taken off the case by a judge, in 2006.

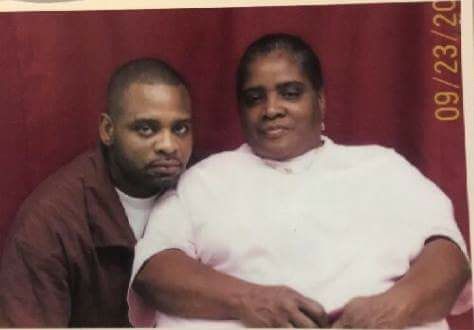

Photo of Nazario Burgos (left) with mother, in Graterford prison.

Nazario Burgos said his family agreed to pay an $8,500 retainer in installments to El-Shabazz to reexamine new evidence related to his life sentence for a 1995 murder, including new eyewitnesses and a tape allegedly featuring state witnesses recanting their testimony.

Although he admits El-Shabazz did file a petition on his behalf, Burgos says that he never heard from him again.

“The facts (El-Shabazz) represented were completely inaccurate and, frankly, made no sense,” he said. “Shabazz was duly being paid, however...(he) never contacted the alibi witnesses or responded to letters or answered my calls.”

Burgos says his family paid El-Shabazz $5,300 before pulling the plug. He blames technical errors in El-Shabazz’s brief for sinking his appeal and filed a judicial complaint against the lawyer. However, the disciplinary board sided with El-Shabazz after he produced logs outlining the time he spent on the case.

Years later, Burgos is still upset. His family today runs a Facebook page called “Right My Injustice” that argues for his release and, in lengthy posts authored by Burgos, publicly criticizes El-Shabazz’s campaign for DA.

“(El-Shabazz) stole my money and, what I paid him to do, I ended up having to learn the law to do it myself. He's up to his predatory practices again. Specifically, visiting prisons in an attempt to convince prisoners to encourage our families to come out and vote for him,” Burgos wrote after the candidate made a campaign pitch while on a recent visit to Graterford. “No matter what he says, he cannot escape his record of betrayal to the people of color he claims to now want to do so much for.”

The timing of these cases notably coincided with declining fortunes and rising financial liabilities for El-Shabazz. Multiple sources linked the money problems that have dogged his campaign for DA to the outcome of cases he took on in the early 2000s, when his client list was rapidly growing.

“He made quite a bit of money initially as a defense attorney. But once he burnt those bridges, the business didn’t come back to him,” Grevious said. “The inmates all talk once they get inside the prison.”

In 2007, Distante, a high-end Center City menswear boutique that specializes in custom suits, filed a $5,000 claim against El-Shabazz in court over unpaid bills. That same year, he allegedly stopped making payments on a $53,000 Lincoln Navigator he’d picked up in 2004. The Ford Motor Company’s credit arm filed another claim against El-Shabazz the following year.

While El-Shabazz would settle these issues, by the time he announced his candidacy, he was hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt to the government and only sporadically paying rent for his law office. Sources in the Public Defenders Association say the veteran attorney began taking court-appointed cases once more, just a decade after representing high-profile figures like drug lord Kaboni Savage.

In a 2012 case, El-Shabazz told a judge that he had blown a trial date in a Montgomery County court because he was busy with another case in a courtroom in Delaware County. When the second judge said they had no memory of seeing him, El-Shabazz was hauled into court on contempt charges.

He insisted he had, despite all evidence to the contrary, been in Delaware County, offering no explanation for the discrepancy.

El-Shabazz “raised his voice, shouted, and refused to answer this Court’s questions as to his whereabouts,” according to a Superior Court decision. “He said his character was being impugned...He argued he didn’t know his conduct was wrongful based on past experiences.”

The court found El-Shabazz in contempt. He was fined $500.

There are good arguments to be made in defense of El-Shabazz, who has had a long and prolific career. He is a man who, by all accounts, can be a compelling and charismatic jurist.

“Any criminal defense attorney is going to have some disgruntled clients. Some may have true cases; some may be exaggerated,” said El-Shabazz’s former law partner, Adam Rodgers. “What I know is that as a litigator, he's a superb attorney. He’s tried thousands of cases and so you're going to have some disgruntled people. But I know him as winning. And people came to him, undoubtedly, because of that reputation.”

Rodgers said he wasn’t familiar with the claims made by some of El-Shabazz’s former clients, but reiterated the unusual stresses placed on high-flying defense lawyers.

“The downside of popularity and fame is taking too many cases. I know a lot of lawyers that’s happened to,” he said.

Despite months of attempts to get El-Shabazz’s side of the story, his campaign declined to comment on the specifics of Brown’s case, or any of the other cases examined in this article.

His campaign stated that he would only discuss Brown’s case if the inmate returned a letter waiving attorney-client privilege – something that Natali said implicitly occurred when Brown brought a petition against El-Shabazz over his conduct. Brown says he never received a letter from El-Shabazz, whom he accused of “playing games.”

After declining to make El-Shabazz available for an interview and abruptly canceling a scheduled interview for an unrelated City&State PA profile, campaign spokesperson Salima Suswell issued a general statement from El-Shabazz in response to requests for comment.

“I made efforts to inquire of Mr. Brown whether he wished to waive his attorney/client privilege and permit me to speak about our communications and I received no response,” it reads. It trumpets his lengthy career and experience over “thousands” of criminal cases, adding that he will “use the judgment that I have developed to ensure that those worthy of a second chance get one.” He only briefly touches on the issues raised by his former clients, mentioning that “Any lawyer with my experience will have moments that can be second-guessed and I accept that, as it comes with the unique life of a trial lawyer that I have been blessed to lead.”

Sitting in prison, Brown said that if he could see El-Shabazz again, he would ask him two questions: “Do you believe Anthony Brown is innocent? And, with hindsight, do you believe that you could have done anything different to defend Anthony Brown?”

Brown’s parents, who still reside in West Philly, are resigned to his fate. His mother, Christine Brown-Miller, worries that the real murderers were a crew of boys from Southwest Philadelphia who have never been apprehended. Boyer believes his son’s enduring hope that his story will somehow earn him a new trial is the only thing keeping him going as he nears two decades behind bars. It’s a hope that is rapidly fading.

Both parents said they were disturbed to watch the man they say failed their son earn headlines for his DA candidacy. They worry about what his election will mean for their son’s case. With appeals exhausted, they believe their son’s last avenue is convincing the district attorney’s office to reexamine his conviction under the unit El-Shabazz formerly oversaw as a deputy to disgraced DA Seth Williams.

They also worry what El-Shabazz’s election could mean for the city.

“I think if the service he gave us is indicative of his service as a DA...” Boyer begins, pausing to search for the right words. Brown’s mother finishes his sentence: “Then we’re in trouble.”

This article has been updated to reflect that Anthony Brown was given a life sentence. He was not give a death sentence, as the story previously read.