Elections (Archived)

How Elizabeth Fiedler beat the odds and the establishment in the 184th

Elizabeth Fiedler, who captured the Democratic nomination for the state House's 184th District. Photo provided.

The evening of May 15, Elizabeth Fiedler gathered with her small team and volunteers in her campaign office at 12th and Tasker streets, a space once better known as the HQ of disgraced former state Sen. Vince Fumo, before it became a doctor’s office – there were still exam tables and scales scattered across the warren of rooms.

From this command center – “(Fumo’s staffers) called it ‘his bunker,’” Fiedler said – the candidate and her team waged an insurgent campaign to win the Democratic nomination for the state House’s 184th District, which stretches across parts of South Philadelphia. She took on – and defeated – the Philadelphia Democratic establishment's preferred candidate, Jonathan “JR” Rowan, an aide to state Sen. Larry Farnese who counted as his main sponsor none other than the politically powerful John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty, boss of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. The district’s incumbent, Bill Keller, announced his retirement in February after 25 years in the seat, and also threw his weight behind Rowan. By beating Rowan and the rest of the field – attorney Tom Wyatt and former police officer Nick DiDonato – and with no Republican on the ballot for the general election in November, Fiedler virtually assured herself a spot in Harrisburg come January 2019.

Part of Fiedler’s success may lie in her former career: she was a radio reporter for a decade with WHYY, first as a stringer and then as a staffer. She partially credits her proximity to power in that role – and her interviews with Pennsylvanians on the issues that most impacted them – with her final decision to announce her candidacy in September.

“As a reporter, I covered education, health care, and city and state politics, and so I got to see firsthand some of the struggles that people had with the education system, the impact of underfunding,” she said. “And I also got to see firsthand a lot of lawmakers and how they set their priorities and their legislative decision-making ... that’s when I really started to think about” running for office.

Prior to WHYY, Fiedler, who hails from Bloomsburg, studied international relations at Bucknell University and worked for six years at several restaurants in Center City Philadelphia. Her only prior political experience was as president of the Board of Governors in 2014 for the Pen & Pencil Club, the social organization for the Philadelphia press.

The oldest of three kids, Fiedler was raised by a middle school teacher and a high school teacher. The discussion of educational politics was a staple in her childhood home.

“Mostly, my parents talked about being teachers and how hard it was: how frustrating it was, their dedication to their students, you know, frustrations with underfunding and the challenges of navigating administration and sort-of educational politics,” Fiedler said. “But politics itself wasn’t really discussed.”

Fiedler says her main impetus in running for public office is her own family. She’s been married since 2004 and has two sons: a 3-year-old and an 11-month-old.

“They are really part of the reason I decided to run,” she said. “As a parent, I feel a lot of responsibility for bringing human beings into this world. Just looking at our trajectory and thinking about where we’re headed politically, and as a state and a country, is really terrifying at moments. There’s a lot of really horrible headlines, a lot of really scary legislation and people with different motives. And I feel a lot of responsibility having these two little people. I decided I wanted to be directly involved in shaping the kind of world that I want them to grow up in … I really felt like I couldn’t rest if I didn’t at least try.”

Fiedler’s campaign manager, Amanda McIllmurray, was a Bernie Sanders staffer responsible for organizing South Philly, and a delegate to the 2016 Democratic National Convention. McIllmurray co-founded Reclaim Philadelphia with fellow staffers after Sanders’ loss in the 2016 Pennsylvania Democratic presidential primary. The group was instrumental in catapulting criminal justice reform advocate and progressive defense attorney Larry Krasner, previously known for his pro bono work for activists, to become Philadelphia DA last fall.

The group, following McIllmurray, mobilized behind Fiedler. In all, the team says that their patchwork foot-soldier canvassing effort – comprised of Reclaim members, returning citizens, volunteers, individual residents, and others – knocked on 50,000 doors in the district and increased turnout in a number of wards.

The team trained to make their outreach more chat than spiel. They trained volunteers to discuss their own reasons for supporting the candidate and to listen to the feedback from their neighbors so they could consider incorporating their concerns into the broader platform.

Fiedler found the support of ideological allies on a larger scale, too.

Fiedler’s vocal support for Medicare for All won her the endorsement of the Philadelphia chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). She racked up endorsements from the Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, Planned Parenthood and Represent PAC, an organization focused on electing progressive women, something Fiedler feels strongly about.

“I do also think a lot of folks want to see more women in office,” Fiedler said. “Pennsylvania is 49th in the nation in women in elected office – second-worst to Mississippi.”

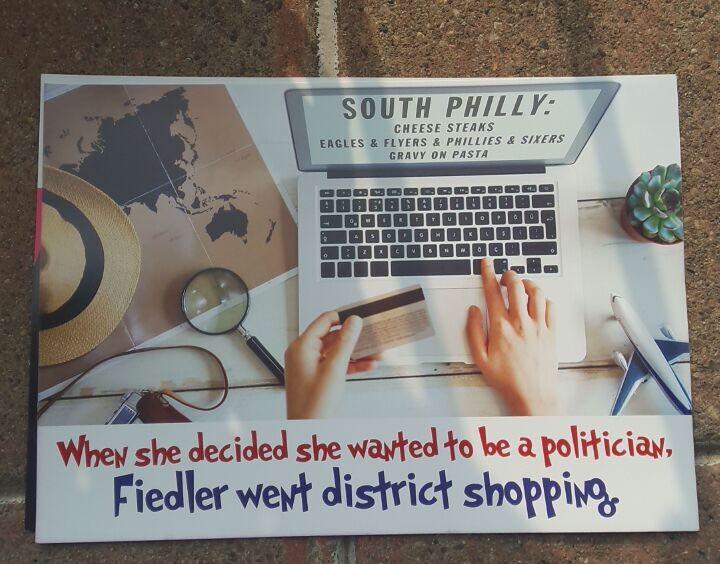

Critics of Fiedler focused on her lack of South Philly bona fides. She moved to the neighborhood in 2014, after 10 years in North Philly. Mailers mocked Fiedler, claiming she went “district shopping,” and zeroed in on the area of residence that would best ensure her a victory.

As Holly Otterbein noted in the Inquirer’s Clout column, the ads were paid for by Friends of Ward 39 – and Jonathan Rowan’s uncle happens to be that ward’s Democratic leader.

One of the mailers sent out attacking Fiedler's lack of long-term residency in the 184th District – photo courtesy Amanda McIllmurray

On primary night, the team gathered in the bunker, nerves tempered only by hopeful anticipation. Volunteers staking out polling places texted and called with snippets of hopeful-sounding information: huge turnouts and long lines in wards they knew were friendly. Those gathered walked from the headquarters to a gathering at Broad and Mifflin above a dentist’s office, where 60 or 70 volunteers grazed on donated food and drink.

On a projector screen, incoming poll results scrolled.

Amanda McIllmurray was there, and as nervous as her boss – but not for long. People who had staked out polling locales began streaming in, sharing their respective intel.

“It seemed like we had blown everybody else out of the water from those results. We were very excited,” she said. “And then we started watching the more official results return online. The numbers kept going up and down – we weren’t sure what was going to happen.”

Fiedler averted her eyes.

“I couldn’t look at it – it was too tense,” Fiedler said. “I couldn’t see (the results), but I could see their faces.”

Katie Longo, Fiedler's field director, shared her butterflies.

“It is very nerve-wracking when you realize all the work that you’ve done for multiple months is played out and all you can do is wait,” Longo said. “After a certain point, I kind of sat off to the side in the back with the computer refreshing the results as polling place information came in.”

“Eventually, we got to a point where we were ahead by a lot and knew which areas hadn’t been counted yet and knew which areas we were expecting to do well in and poorly in,” McIllmurray said. “And we felt confident in saying ‘Yeah, we actually won this thing.’”

Fiedler still has trouble finding the right words to express her victory.

“Surreal,” Fiedler said. “It was so celebratory – we were all so exhausted from working so hard. And we ran a campaign that we could be proud of. No deals, no shortcuts – nothing like that. We always said that no matter what, we would run a campaign that we would be proud of – and then we also won.”

Any progressive proposal Fiedler brings to Harrisburg starting next year could be a Sisyphean task: 119 of 203 representatives are Republicans. Of 50 senators, 34 are Republicans, and November could see the election of a Republican governor, Scott Wagner.

Her solution: creative coalition-building. She’ll be reaching out to new faces and incumbents, she said.

“OK, this problem has been approached from one direction or one perspective: can we step back and think of new things?” she asked rhetorically. “Is there a different way to go at this? Can we build a broader coalition to make this happen?”

Beyond that, she plans on returning to her district frequently to reconnect with constituents. To hear; to listen. She needs to.

Town halls "will be in the district and I think that those will be real opportunities both to hold me accountable for some of these things and also for (voters) to let me know they’ve got my back,” Fiedler said. “I’m going to encounter some resistance in Harrisburg and I’m going to do that on behalf of the people of South Philadelphia.”

NEXT STORY: Winners and Losers for the week ending June 22