Analysis

How Philly’s ward system works and doesn’t work – and what is being done to change it

City & State spoke with experts who offered a glimpse into this complex electoral process.

Committee person Justino Navarro canvasses his neighborhood. Philadelphia 8th Ward Democratic Committee

Local elections matter – just ask anyone familiar with Philadelphia’s antiquated ward system. While most large cities have shed their old electoral subdivisions, the City of Brotherly Love is somewhat unique in that its political superstructure still operates through a ward system.

Wards are individual voting districts within the city, and within each ward are multiple districts, more commonly known as precincts. To offer an explainer of the ward system, City & State spoke with experts including former and current committee people and the former city commissioner. They offered a glimpse into the electoral process, how it influences votes and why a newer generation of advocates is looking to open wards and the process as a whole.

How it works

Philadelphia’s ward system dates back to the 1700s, when it was reportedly implemented as a way to organize police routes. As the city began to grow, so did the number of wards, and by 1966, a re-division of ward lines created the system that we see today.

The city is composed of 66 wards, or political units, and each ward is broken down into various divisions. A ward is the smallest political unit when it comes to taxes and elections that is still divisible by voter registration numbers. Every four years, voters in each of the 1,703 divisions elect two committee people for their party, and two Democrats and two Republicans from each division make up the ward committee. Once each committee is established, committee people in all 66 wards reorganize to elect ward leaders, and ward leaders then elect the chairs of their respective City Committees.

The most recent primary election marked a new election cycle, with committee people and ward leaders being elected during reorganization on June 6.

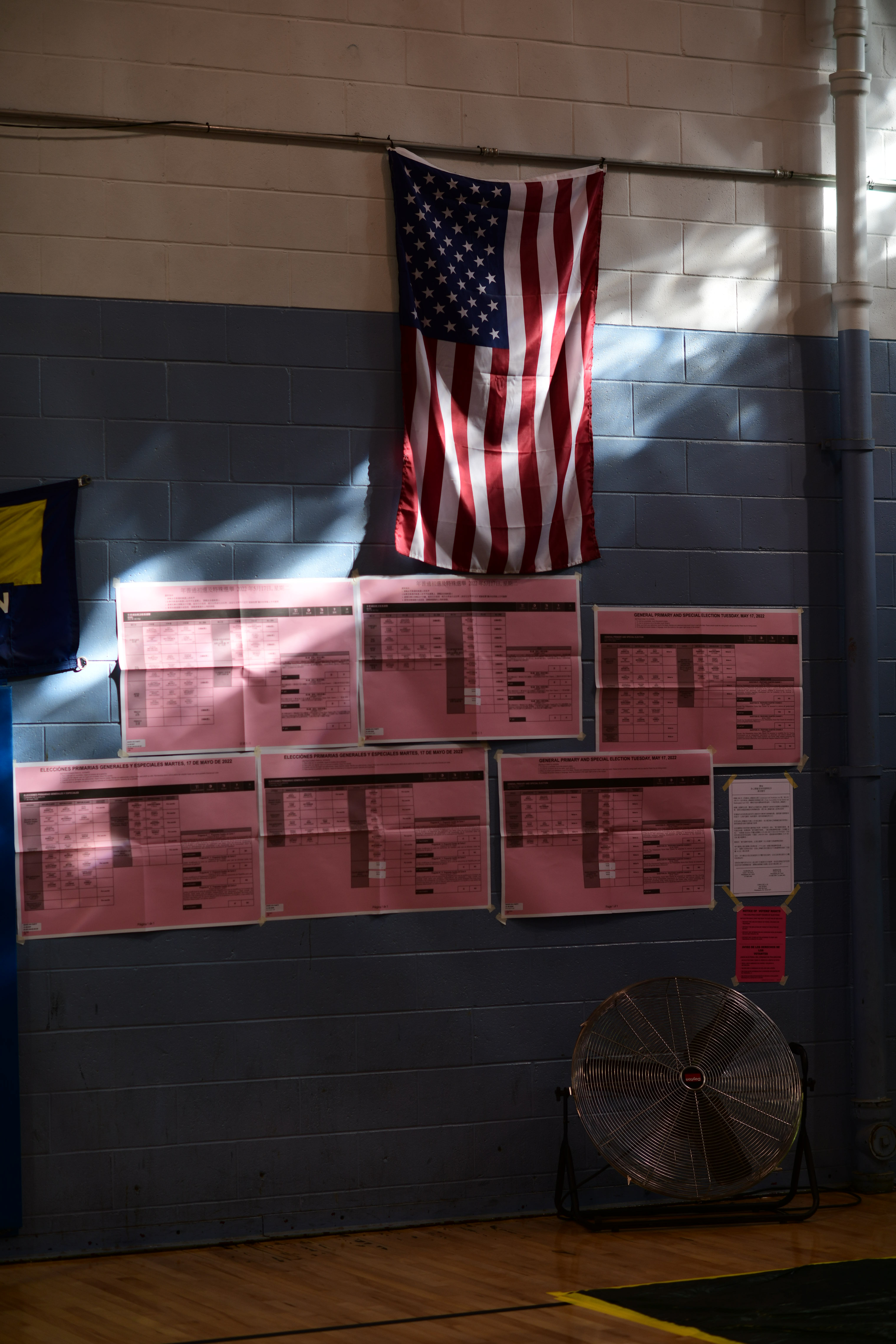

Once elected, ward leaders and committee people have responsibilities to their party. Committee people have responsibilities similar to a neighborhood block captain. The committee people from each party are foot soldiers for their committee, doing anything from registering and reminding neighbors to vote to sharing candidate endorsements and helping staff polling places.

Ward leaders are also tasked with staffing polling places in each division. Their responsibilities include recruiting committee people for open seats, raising funds, and arguably most importantly, endorsing candidates and engaging voters.

That endorsement power is even more important during special elections, where party nominees are solely selected by the City Committees rather than the voters themselves. And in a city where Democrats outnumber Republicans by up to 7-to-1 in some areas, that special election nomination can be the Democratic City Committee handpicking its preferred lawmaker.

“Unsurprisingly, ward leaders usually pick amongst themselves,” Al Schmidt, former city commissioner and president & CEO of the Committee of Seventy, told City & State.

It’s within this part of the ward system, where party leaders have entrenched themselves, that the city has run into some issues. In closed wards, committee people don’t have a direct say in the endorsement process and ward leaders can make decisions on their own. In open wards, candidates can make their case to committee people. In these open wards, the endorsement is based on a vote and committee people who don’t support the nominee are given the opportunity to share their own endorsements.

“Those committee people, as a body, should ultimately make the decision around who is going to be the candidate that best reflects the interests of our community,” Quetcy Lozada, community organizer and former committee person in the 33rd ward, said. “I think that committee people don't recognize the power that they have and oftentimes are led by what the ward leader says should happen.”

Ward leader endorsements are significant not just during special elections but in all down-ballot races too, Schmidt said. Voters may have research and opinions on statewide or legislative races where they recognize the candidates, but many rely on the sample ballots handed out by committee people at the polls for information on the down-ballot races such as for municipal or common pleas judge.

“Down ballot you have more obscure races,” Schmidt said. “In those down-ticket races, there aren’t millions of dollars spent on advertising. It's with those candidates – where committee people working outside of the polls and handing someone a piece of paper with a name on it – that they can have the biggest impact.”

In an open ward, committee people can distribute their endorsements if they don’t support the committee’s nominee. And in neighborhoods where committee people are engaged with the voters, that personal endorsement could go a long way.

“When a committee person has been in education for a while, people know that committee person, they trust that person and they rely on them for recommendations,” Karen Bojar, former committee person in the 9th ward and author of the book “Green Shoots of Democracy within the Philadelphia Democratic Party,” said. “The only way to educate people and to encourage civic engagement is to give committee persons themselves some power within the ward.”

Open v. closed wards

Offering committee people that endorsement power is one of the reasons Philadelphia has seen another push by community organizations to create more open wards. The city had a handful of open wards prior to 2018, but Bojar said grassroots work from organizations such as Reclaim Philadelphia boosted the election of a new wave of committee people seeking a more democratic system.

The 2018 ward elections led to new leadership in several wards and to the city doubling its number of open wards. In the most recent reorganization, wards including the 15th, 24th, 30th and 39A are expected to join several other of the city’s open wards. Most recently, the 1st, 2nd, 18th, 48th and 51st wards, all of them Democratic, joined the likes of the 5th, 8th, 9th, 27th and 30th wards as the city’s open wards.

Aside from candidate endorsements, having open wards ensures committee people can vote on policies, allow the public to attend meetings, and track campaign finance reports, among other things. These mechanisms allow for greater transparency and accountability, said Michael Swayze, committee person in the 22nd ward and a member of Open Wards’ steering committee.

“The best way to clean (the system) up is by electing committee people who want openness, democracy and transparency,” he said. “These days, it seems that the political system is somewhat tired because the ward system that we have now doesn't seem to be responsive to many of the people that I associate with within the grassroots community.”

Swayze is among several newly elected and longtime committee people behind the Open Wards Project, an effort that seeks to create a better ward system in Philadelphia.

Swayze said the 22nd ward, led by ward leader and City Council Member Cindy Bass, has been an example of a community where committee people were shut out of the process and now a new generation wants to get more involved.

“(Bass) thinks of us as an organization, but we’re not. We’re a caucus, a committee of people who want to be able to have the tools to be able to do the job and who want to be foot soldiers for the Democratic Party,” he said.

The 22nd ward saw a 50% turnover rate among committee people in 2018, and in the most recent election, 23 of the ward’s 58 committee people will be newly elected. “There seems to be a bit of replenishment with new blood. Philadelphia needs new blood,” Swayze said.

Philly’s Future

What does that new blood look like? Much like the political makeup of the city, the movement toward open wards has been amongst the Democratic Party. But for the most part, the push for open wards is a result of those within the party bucking the party’s establishment.

The splintering within Philadelphia’s Democratic Party was no more apparent than the primary election, where the City Committee’s endorsements, mainly moderate candidates, lost to more progressive candidates. Bojar said the Democratic Party’s efforts to block progressive candidates rather than listen to its voters proved that the party establishment is “crumbling.”

“The system of feedback, from the community to ward leaders to the party chair, that democratic structure isn’t working,” she said.

Bojar added that the election of committee people willing to create open wards has occurred mostly in areas where voters are both educated and engaged. “Orchestrating a ward takeover takes a tremendous amount of effort. I think it's worth it because we're a one-party town. It’s so important to clean up the Democratic Party and ensure it’s open and transparent.”

The benefits of electing a dedicated committee person are twofold. Not only do voters know that the individual is engaged and informed, but they’re also in line with their neighbors and can be a proper representative of the community.

“You may have a committee person who’s more interested in the job because they're really ideologically driven, as opposed to someone who became a committee person hoping they'd get a recommendation for a job to work in some city agency,” Schmidt said. “Having more ideologically driven people means they're a lot more dedicated than someone who’s trying to get or keep a job.”

The need for newcomers goes beyond system reforms and proper representation, however. As almost every county in the state experienced, Schmidt said, Philadelphia has a shortage of poll workers. And with a large portion of poll workers and committee people being retirees, the stakes for finding residents interested in taking part in the democratic process are even higher.

Lozada said she’s witnessed Election Days where leadership from the top down failed to organize, and that these disjointed processes can deter people from wanting to participate.

“In many divisions, there is extreme chaos (on Election Day). It doesn’t matter if it's the committee person, if it’s a ward leader, if it’s the clerk or the judge on the division. It is just total chaos,” she said. Aside from better organization from the party and ward leadership, Lozada said the city can do more to provide accurate information to everyone involved in the process. “I think there has to be clarity … around what should and should not be done in every election cycle.”

Recent elections and the movement to create more open wards are signs that the changing of the guard could be coming. As a longtime committee person and ward system expert, Bojar said newcomers must have the energy and commitment to go door-to-door and educate their communities. Whichever groups in the younger generation can garner support and organize will be in a great position to take over the next couple of election cycles.

“It’s hard to find a whole lot of people in one specific area who are ready to work together at one specific time because it’s so labor-intensive,” Bojar said. “Most committee people started from the late 60s through the 90s, so obviously they cannot continue (much longer). There will be a generational change or a technical collapse.”