Transportation

Losing their routes: PA’s transit funding crisis looms over rural systems

After years of ridership and funding issues, rural transit systems hope lawmakers will pony up so they can avoid service cuts.

Transit stakeholders rally at the state Capitol in Harrisburg on June 4, 2025 to call for a dedicated and expanded transit funding solution. OFFICE OF STATE SEN. NIKIL SAVAL

The roads less traveled still rely on public transportation.

All the transit talk in Harrisburg has been focused on the commonwealth’s two biggest cities – Philadelphia and Pittsburgh – and the need for state funding to support their public transit systems.

But, as many transit advocates have pointed out during rallies, there are public transit systems in all 67 counties in the commonwealth.

And while the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority and Pittsburgh Regional Transit move the most people and are facing severe cuts, suburban and rural systems from the Lehigh Valley to Erie – and everywhere in between – face similar financial challenges and are seeking answers as the state budget looms.

Much like their urban counterparts, the commonwealth’s other transit systems are hoping to maintain their existing service amid dire financial straits. Several regional public transit systems in rural counties are facing tough decisions – including potential service cuts, fare increases or both – all while the state’s shared ride program is facing a potential $70 million shortfall.

As these systems consider raising fares and cutting service routes – which are essential for residents with disabilities, on low incomes, or who are elderly – local advocates are trying to highlight the importance of transit in smaller, often isolated communities.

“It’s a myth to assume that transit exists in isolation,” Connor Descheemaker, statewide campaign manager for the advocacy organization Transit for All PA, told City & State. “Transit is interdependent, and it needs to have support.”

Transit’s track record

Since Act 89 of 2013 – the most recent transportation funding package that sought to support and advance public transportation across the commonwealth – public transit agencies have been funded through a variety of channels, mainly motor vehicle fuel taxes.

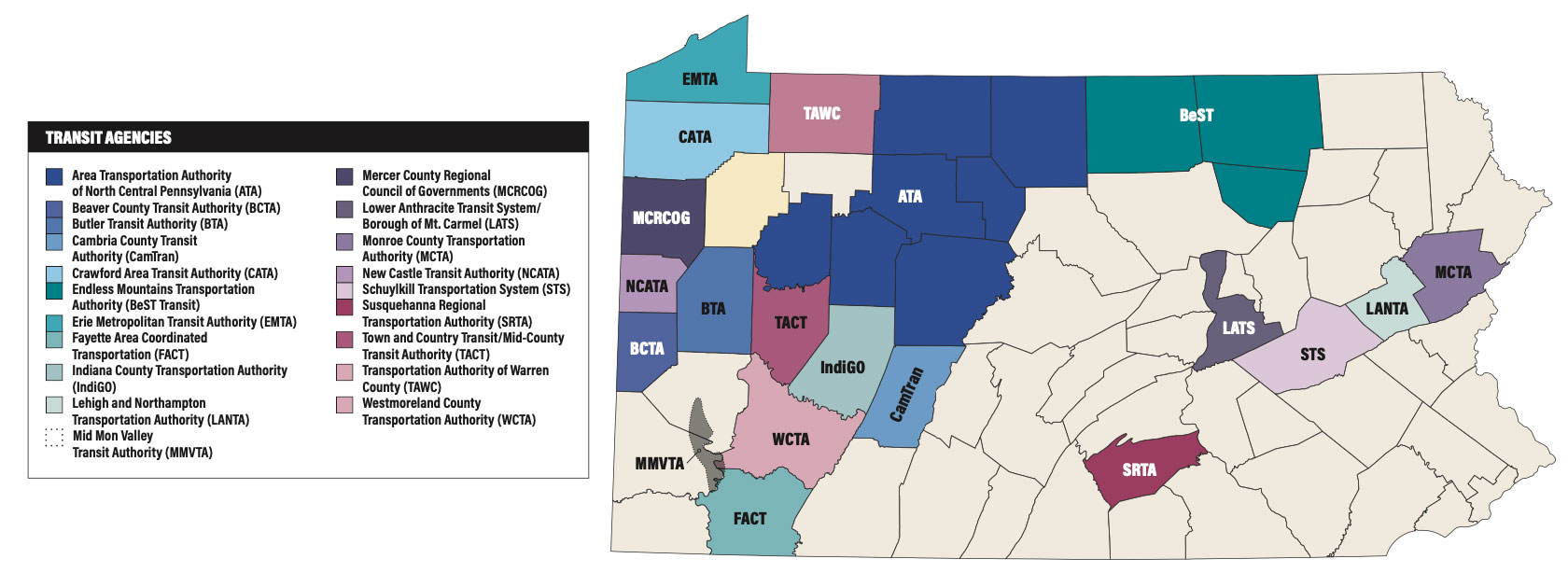

Statewide, there are 53 public transit agencies across the 67 counties, with more than 45,000 trips occurring daily outside the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh systems.

The commonwealth funds 20 rural transit systems, which can serve areas with a population of less than 50,000. These systems, while including parts of the Lehigh Valley, Northeast and Central Pennsylvania regions, largely serve tough-to-reach areas of Northwest and Western Pennsylvania.

There are also community transportation systems that provide ride-share services and demand-responsive transportation to human services programs, which extend beyond typical transit times and service areas. Often used by the elderly and people with disabilities, these services provide crucial connections for those who may be experiencing isolation, as well as those in need of a lift to a medical appointment or a store.

Craig Beavers, vice chair of the Allentown City Planning Commission and a Lehigh and Northampton Transportation Authority rider, said service cuts on weekends, especially Sundays and late-nights, would have a significant impact on workers and residents.

“Anyone who has to go anywhere on the weekend is stranded, unless they own a car or have the ability to walk to the destination,” he said. “Our seniors are going to have a lot of major impacts to their lives. They won’t be able to get to their doctor’s appointments, won’t be able to go to the grocery store to get their food, and it’s very possible that we might be seeing a major health crisis for some of our elderly population.”

Alex Casper, a McKean County resident who relies on public transit to get to medical appointments in Western Pennsylvania, told City & State that the proportion of people who rely on transit services and have a disability is high.

“The Area Transportation Authority of Northern Central Pennsylvania is the most proportionately disabled-service provider that covers more than one county,” Casper said, adding that potential service cuts would hurt the community on multiple levels. “The only service provider that is more proportionately disabled is my neighbor, Forest County, which is a single-county transit system … You can imagine the impact that’s going to have on rural communities’ economies, when you know there’s 15,000 (fewer) customers every year for the businesses.”

Joan Monroe, a Westmoreland County resident who’s been outspoken about public transit, told City & State she’s heard from seniors and families that a local bus route is often the only means of getting to the grocery store.

“We have a senior building, a residence called the Trafford Manor. People use that bus to go to the grocery store, which is across the bridge. It’s six-tenths of a mile from the grocery store,” Monroe told City & State. She added that she’s been joined by other residents in getting petitions signed at the grocery store and senior center to call out the impact of bus service cuts. “An Uber driver came up to us and said, ‘Sometimes I take people from your senior building to this grocery store.’ I said, ‘How much does that cost?’ (He replied) ‘$15 for six-tenths of a mile.”’

Thanks in part to rising costs, ridership still below pre-pandemic levels and federal relief funding running out, transit systems across the state are facing structural deficits.

LANTA in the Lehigh Valley is projecting a 20% service cut and a 25% minimum fare increase. Rabbittransit, which serves York County and CATA in Centre County, will have to seek fare increases, and systems in Cambria, Erie and Jefferson counties are all facing further service cuts.

And covering parts of Washington and Westmoreland counties, the Mid Mon Valley Transit and Freedom system says it is facing funding deficits in coming years and needs increased state funding just to maintain existing levels of service.

At the same time, PennDOT ranks fourth in the nation for direct support in funding public transportation, with approximately $1.5 billion allocated to the public transportation trust fund as of 2023.

“We get that public transportation is an essential service,” Republican state Sen. Judy Ward, chair of the Senate Transportation Committee, told City & State, noting PennDOT’s existing investments in transit. “Five years post-COVID, our ridership on SEPTA and PRT really has not fully returned. We want to make sure they’re right-sizing their routes and their staffing and their spending.”

Ward, who represents parts of Blair County, where the Altoona Metro Transit system operates, said rural communities “want some fairness and equity in funding.”

“No one’s going to be happy with cuts to anything, but I do think the people of Pennsylvania really appreciate us being diligent and thoughtful about where money goes and looking at metrics of your performance,” Ward said.

Plenty of plans

Proposals on each side of the aisle have targeted public transit funding. In his budget plan, Gov. Josh Shapiro proposed a 1.75% increase in funding for transit systems statewide, which would bring in a total of nearly $300 million for systems statewide.

Shapiro and House Democrats have expressed support for using skill games revenues to fund transit, but opposition from casino operators and differences over the tax rate on the devices has so far proven to be a stumbling block.

And while Senate Republicans agreed to a one-time funding increase of $80.5 million for mass transit, roads and bridges throughout the state in last year’s budget, which included roughly $51 million for SEPTA, they haven’t been on the same track as Shapiro this year.

The Democrat-led House passed state Rep. Ed Neilson’s House Bill 1364, which would enact Shapiro’s plan to support mass transit in all 67 counties by increasing the percentage of sales tax revenue allocated to the Public Transportation Trust Fund from 4.4% to 6.15%. If passed through the Republican-controlled Senate, the plan would result in an increase of $292.5 million in funding next year and $1.5 billion over the next five years, Neilson said.

Any transit funding would have to be either paired with or passed alongside funding for road and bridge repair. Any other proposal, Ward said, is a nonstarter.

Democratic state Sens. Nikil Saval and Lindsey Williams introduced a “Transit for All” funding package that would increase the state’s daily car rental fee from $2 to $6.50 and the state’s car lease fee from 3% to 5%. It would also establish a 6% excise fee on transportation network companies, or rideshare apps, such as Uber and Lyft.

Advocates stated that $537 million is required to restore transit service statewide to 2019 levels, adjusted for inflation, with an additional 10% service expansion in regions outside of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Republicans in Harrisburg, while recognizing the need for additional transportation funds, have their own ideas. State House GOP leader Jesse Topper announced a plan to allow a public-private partnership to help SEPTA address its fiscal shortfall – a move he said would lessen financial strains on the system.

Ward said the budget negotiations are still “pretty fluid,” with several potential revenue sources, from rental and ride-share fees to tax revenue from the potential regulation of casino-like skill game machines, all on the table.

“There are competing priorities from both chambers, and I think we have a duty to invest all taxpayer dollars wisely, so it’s a real balancing act,” Ward told City & State.

Those in the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh areas may be surprised by Ward’s hesitancy to fund their public transit systems, but she is arguably one of the more moderate Republican voices in Harrisburg on the issue, as evidenced by numerous parts of a statement by state Sen. Cris Dush on June 10, where he voiced opposition to additional transit funding for cities and called SEPTA operators “chauffeurs.”

“Many of our people are driving 60 miles each way to work in an area where the median family income is significantly lower than that in the SEPTA service area. You are taking money from an area made poor by the decisions to pull our tax dollars to your area while you have the luxury of being able to sit on a bus or train catching up on work or social media while our folks must pay attention to the road ahead to avoid deer and other drivers,” the letter said. “I will not take from the infirm, the elderly to provide money for SEPTA nor will I ask those who have never used SEPTA to sacrifice their own transportation infrastructure (like Governor Shapiro did to us) for one as poorly managed as it was under (former SEPTA General Manager) Ms. (Leslie) Richards.”

Transit’s next stop

At publication time, lawmakers still hadn’t given an indication what transportation funding will make it into the budget.

With talks tied to roads and bridges, Democrats and transit advocates are making the case that taxpayer dollars are spread throughout the commonwealth – so if a funding package comes together, every community could benefit.

“We’re constantly reminding (Republican legislators) when they say, ‘Well, our constituents don’t ride on your system, so why should we invest?’ that our constituents will probably never ride on your roads and bridges, but we are still forced to invest” in them, state Rep. Morgan Cephas, chair of the Philadelphia delegation, said during a June 5 public hearing on transit. “We have to ensure as a commonwealth that we’re looking at the entire state in order for us to be economically viable, to be a destination for businesses, a destination for families … It’s mass transit for us, but it’s roads and bridges for you all as well.”

Beavers, who argues that having fewer transit options would result in more cars – and, in turn, more congestion, accidents and pollution on the state’s roadways – said the downstream effects of a lack of accessible transit will be felt across Pennsylvania.

“If we don’t address the transit issue, then we’re going to have more impacts on our roadways and our bridges and other infrastructure,” Beaver said. “It’s a death spiral.”