Education

Fair funding fallout

A look back at the state’s education funding trial and where the General Assembly can go from here.

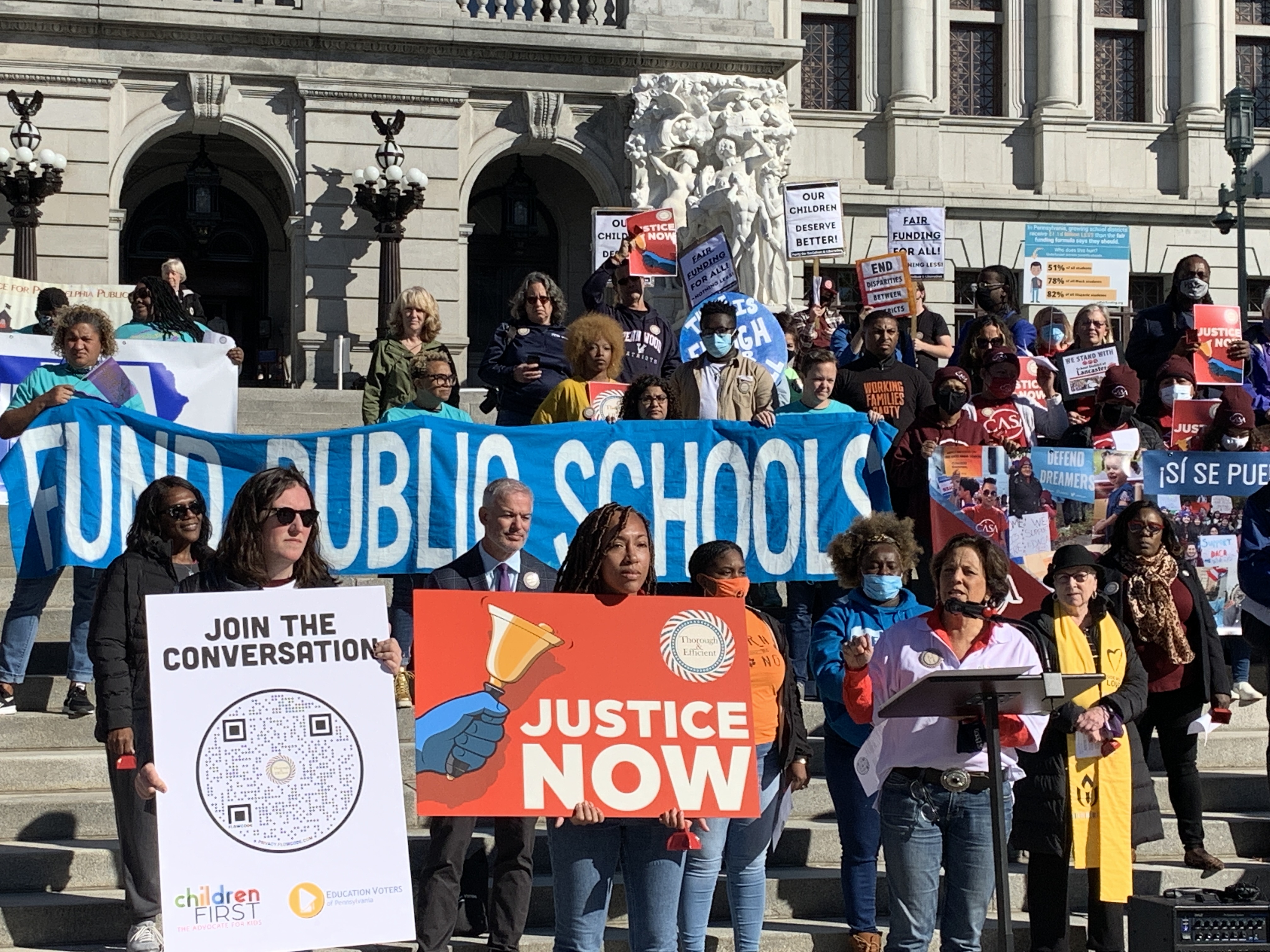

Tomea Sippio-Smith and others like her argue state schools are grossly underfunded and fail to meet basic minimums. Children First

The school year may be winding down, but education policy discussions are just ramping up for the summer.

The commonwealth’s landmark public education funding lawsuit went from a complicated, seven-year process to a four-month trial. It came to a close last month.

As the petitioners – which include six school districts, four parents and two statewide organizations – await a decision from Commonwealth Court Judge Renée Cohn Jubelirer on whether the state and legislature are meeting the state constitutional requirement to provide “for the maintenance and support of a thorough and efficient system of public education,” it’s instructive to assess both the trial and what the potential outcomes could mean for the General Assembly and school districts.

How we got here

Throughout the trial, the petitioners argued that school districts around the state are underfunded and fail to meet the needs of students. Specifically, two legal claims were made. The first alleges that the state’s school funding fails to provide the adequate education outlined in the state constitution, and the second alleges the funding violates Equal Protection provisions in the state constitution because it discriminates against “an identifiable class of students who reside in school districts with low incomes and property values.”

“It’s so clear from the clients we serve – rural, urban, suburban, Southeast Pennsylvania, Western Pennsylvania, Northeast, and all over the state – our students are attending predominantly underfunded schools. And that disproportionately impacts our Black and brown students,” Deborah Gordon Klehr, executive director of the Education Law Center, told City & State. ELC, alongside the Public Interest Law Center and private firm O’Melveny, are arguing the case on behalf of the petitioners.

Defendants in the case, representing state House and Senate leadership, refuted these claims by arguing that the state spends more per capita on education than most other states.

While that may be true, Pennsylvania still has some of the widest spending gaps among wealthy and poor districts in the nation. The commonwealth also contributes less as a state to overall education spending. Pennsylvania contributes 38% of education spending in the state, compared to a national average of 47%. That ranks the commonwealth 44th in the nation for its share of funding for public schools, according to the Pennsylvania School Boards Association.

Exhibits from petitioners in the case displayed everything from hallways or portable spaces converted into classrooms to deteriorating facilities and equipment. Klehr noted instances where, in the Greater Johnstown School District, 125 children in one grade are sharing one toilet and middle schoolers are using textbooks showing Bill Clinton as the current president.

“If schools were adequately funded, all students would have the educational opportunities needed to be college- and career-ready,” Klehr said. “Those are the opportunities students and wealthy districts have now.”

Attorneys for Republican legislative leaders said the case is about the constitutionality of the school system – not whether it’s an ideal situation. Eric Hanushek, a fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and an expert witness for the Republican leaders, said education funding doesn’t directly correlate with academic achievement.

“Sometimes, people spend money and get really good results, and sometimes they spend money to get really bad results,” Hanushek told City & State. “There’s no systematic relationship from just providing money to (getting good) outcomes.”

Klehr acknowledged that litigation isn’t going to directly create equitable funding policy, but she said other states have shown it’s a viable way to get the wheels turning.

“What we see is that school funding lawsuits in other states have spurred more revenue for public schools, reduced inequality and led to better academic and life outcomes for students,” she said. “You look at other states without litigation, and (policy is up to) who’s in leadership at that time – not necessarily the actual needs of the students.”

If the court were to rule in favor of the petitioners, legislators would be sent back to Harrisburg with the task of having to revamp the state’s school system.

What’s at stake

But what are the biggest challenges for schools and administrators right now? Attorneys from both sides argued whether past assessments offered an accurate picture of the disparities that exist in public schools.

A new report from the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators and PSBA gives a glimpse of the school system today.

The 2022 State of Education Report, developed by PSBA and PASA, was released on April 12. The report, which includes surveys of school administrators and parents, as well as data from the state department of education, found that schools are facing unprecedented staffing and budgeting shortfalls.

Ninety-nine percent of school districts reported experiencing a shortage of substitute teachers and about 80% reported shortages in instructional aides and bus drivers. Not far behind were concerns over health and safety, specifically inadequate and ever-changing guidance throughout the pandemic. And for the third consecutive year, mandatory charter school tuition payments were the top source of budget issues.

There’s no argument more resources would be needed to help school districts overcome these challenges, but the question is over the best method to directly address them.

Hanushek said increasing teacher salaries is one way. However, he said, a broad increase in teacher salaries isn’t a silver bullet.

“Bad teachers like more money as much as good teachers,” he said. “We know from undisputed research that the effectiveness of teachers is extraordinarily important. So systems that identify effective teachers and provide effective teachers to disadvantaged kids that are poor-performing are ones that have closed the achievement gap.”

Hanushek suggested implementing a teacher evaluation system similar to the IMPACT program in Washington, D.C., where teachers with highly effective ratings are rewarded with bonuses and ineffective teachers are pushed out. “It’s hard to devise regulations that say, ‘Go do good,’” he explained as his rationale for accountability and incentive measures.

What comes next

Findings of facts and conclusions are due at the end of the month, and amicus briefs from outside parties are due May 6. Post-trial briefs will be concluded by July 6, at which time Jubelirer could make a ruling or order additional oral arguments over the summer. Regardless of the outcome, the losing party is expected to appeal to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

If Jubelirer rules in favor of the petitioners, lawmakers will have to go back to the drawing board to create a school funding system that allows all school districts to meet academic standards. Klehr said she hopes any redesign of the state’s education funding system starts with a needs assessment and works in transparency mechanisms from there.

“Any rational system would start with an effort to figure out how much state funding schools need to be able to provide essential educational support,” she said. “The court isn’t going to come up with what that system is. We would hope that the court would exercise oversight over the process to ensure accountability of the General Assembly to meet its constitutional duties.”